Growing Russia-China Bonhomie

A new alliance in the making?

Russia’s policy towards China has been one of adaptation and accommodation. Despite increasing asymmetry in power between the two states, Moscow and Beijing have reinforced cooperation and managed to overcome a number of challenges. These included Russia’s policy towards Ukraine, Moscow and Beijing’s competing regional projects in Eurasia and China’s growing activity in the Arctic. China and Russia coordinated their efforts in a number of domains, primarily in the global realm. Recently, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army joined Russia and six other nations for Tsentr 2019, a massive, five-day military exercise involving over 100,000 troops. Just last year, Russia and China joined in the Vostok military exercise with over 300,000 troops in Siberia training jointly near the Chinese border. These exercises are the clearest evidence, to date, of how Russian-Chinese relations have grown increasingly close since the Sino-Soviet split in 1961, when Moscow and Beijing were competing for control of the communist world. Having significantly expanded their economic, military and diplomatic ties, both countries see value in an alliance against their common enemy — the United States. Moreover, pressure they have been putting on the West increased each state’s room for manoeuvre in international politics.

The most popular topic in modern geopolitics these days is probably the budding relationship between Russia and China. Articles on the subject are produced regularly, almost all of them concluding that Russia is only temporarily siding with China. It is just a matter of time, these articles claim, until disagreements between the two powers become inevitable. These articles miss the fact that Moscow’s move away from Europe is rooted deeply in Russian history. Moreover, Russian-Chinese partnership is built around their common animosity toward the US. Both have been confronted by the US and have taken actions that go against Washington’s worldview, which favours a division of the Eurasian landmass among multiple powers and the maintenance of control over the world’s oceans.

All-out efforts by Western actors, particularly the United States, aimed at containing the rise of China in East and Southeast Asia, and Russia in the wider Black Sea and the Middle East has further brought Moscow and Beijing closer. China is a major purchaser of Russian military equipment, which has been critical to modernizing the PLA. China also relies on Russia’s vast oil and natural gas reserves. Trade between the two countries is projected to rise to $200 billion by 2020.

In addition, since taking office in 2013, Xi has visited Russia eight times and met with Putin more than 30 times on bilateral and multilateral occasions, demonstrating strong friendship and political trust between the two heads of state against the background of a turbulent world. More recently, in September, defence ministries of Russia and China announced that the two sides have drafted a new cooperation agreement for 2020–2021. The agreement will add yet another weld bead to the bond that joins Russia and China together.

So is an unbreakable alliance now in the making between Russia and China?

Relations between the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War era ebbed and flowed. For example, bilateral relations during the late 1940s and throughout much of the 1950s were cordial. Despite a certain degree of rivalry between Moscow and Beijing for the leadership of the communist world globally, Russian and Chinese leadership saw great benefit in cooperating across the board with a view to contesting the primacy of the U.S.-led Western camp.

Following American strategic overtures toward China in the early 1970s, the bonds between the Soviet Union and China weakened. In line with realpolitik strategic thinking, the American decision-makers during the Nixon presidency wanted to drive a wedge between these two communist behemoths. While the famous ping-pong diplomacy of the Nixon presidency under the stewardship of National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger paved the way for a strategic rapprochement between the United States and China, relations between the Soviet Union and China deteriorated. The prime goal of the United States in helping facilitate China’s opening to the international world was to weaken the so-called Soviet-Chinese axis.

Unlike the Cold War era

The end of the Cold War has ushered in a new understanding in bilateral Russian-Chinese relations. Since the early 1990s till now the degree and scope of cooperation between Russia and China have spectacularly grown. Unlike the Cold War era, these two great powers have begun defining their relationship increasingly from a strategic point of view. Their common strategic goal has been to limit the influence of the United States in the greater Eurasian region.

Despite increasing cooperation, relations with China did not occupy the center stage in Russian foreign policy during the 1990s, mainly for two reasons. First, post-communist Russia under the presidency of Boris Yeltsin adopted a pro-Western foreign policy orientation. Russia undertook many liberal reforms at home while yearning for the recognition of its Western identity by Western powers. Despite all its opposition to the enlargements of NATO and the European Union toward closer to its borders, Russia’s declining material power capacity on the one hand and the willingness of the Russian leadership to become a legitimate member of the Western world on the other limited Russia’s reactions in this regard.

Second, China was at the early stages of its economic development process during the 1990s and was in no position to appear as a reliable trade partner and a source of financial investment for the Russian economy. China adopted a reactive and low-key foreign policy orientation and saw its relations with the United States key to its economic modernization. Both Russia and China valued their relations with Western actors more than their relations with one another and none of them were in a position to appear a reliable strategic partner for the other.

Putin as game-changer

Putin’s coming to power in the late 1990s boosted the determination of Russian elites to help rejuvenate Russia as a great power with growing economic and military capabilities as well as a distinctive sphere of influence. Increasing oil and gas revenues on the one hand and Putin’s success in strengthening state capacity on the other have proved instrumental in the revival of Russian power over the last two decades. In parallel to spectacular increases in its material power capability, Russia has simultaneously adopted an assertive foreign and security policy line aiming at delegitimizing the core tenets of the liberal international order. Russia’s war with Georgia in the summer of 2008, its annexation of Crimea in 2014, its support to pro-Russian separatists in Eastern Ukraine, its military involvement in Syria in late 2015 on the side of the incumbent Assad regime and its ongoing efforts to meddle in the internal affairs of some liberal Western countries through the hybrid tactics of political warfare have put Russia on a collision course with the Western world.

Russia’s recent strategic rapprochement with China cannot be understood without taking into account the dramatic negative turn in Russia’s relations with the West. Russia’s relations with the United States have reached its nadir following the alleged claims that Russia interfered in the U.S. presidential elections in 2016 by overtly working for the success of one candidate, Donald Trump, at the expense of the other, Hillary Clinton. Despite all the intentions of President Donald Trump to help improve relations with Putin’s Russia, both the Congress and the majority of the American public alike have now adopted a negative tone toward Russia. Despite Trump’s transactional approach toward European allies and extremely critical stance on the value of NATO, American contributions to NATO’s deterrence and reassurance capabilities have also dramatically increased over the last five years.

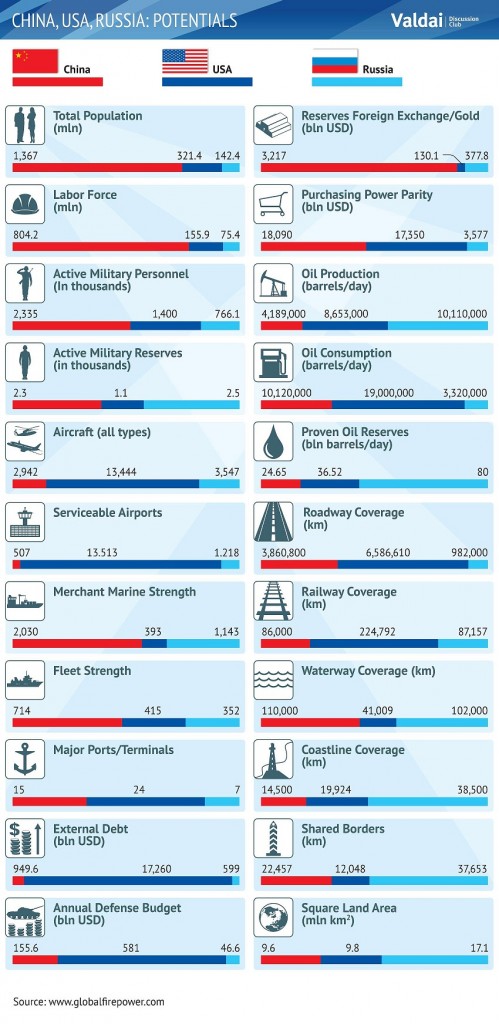

Russia’s strategic rapprochement with China has also been driven by the worsening of relations between China and the United States over the last decade. According to Graham Allison and many other structural-realist scholars, it is highly likely that a war will occur between the established global power and the rising power because the established power would not want to lose its hegemony and privileges within the system emanating from its unrivalled power status. By this logic, if the United States does not want to see its global hegemony be put under threat in the years to come, it would do well to help contain China’s rise now. Therefore, the downward spiral in American-Chinese relations can be attributed to the meticulous rise in China’s material power capabilities relative to those of the United States and the fear this has instilled in American decision-makers.

The current Chinese President Xi Jinping defines the Chinese dream as the rejuvenation of China as the most powerful country in East Asia and the end of China’s century of humiliation at the hands of Western powers. The dream also contains China’s wish to overtake the current global hegemon, the United States, in all critical power categories by 2035. While China has adopted a more nationalistic and assertive foreign policy line by leaving the decades-old “hide your capabilities and bide your time” dictum behind, the United States has begun interpreting the rise of China as the most important challenge levelled against its national security and global primacy.

Today, the Trump administration has been pursuing a protectionist trade war against China while increasingly trying to contain its rise through the adoption of the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy and boosting the military capabilities of its traditional allies in the region. Contemplating alternative development strategies to rival China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has also become a part of the American playbook.

Russia and China are both realpolitik security actors that believe in the primacy of hard power capabilities and tend to define security from the perspectives of territorial integrity, national sovereignty and societal cohesion. Both countries believe that the unipolar era between the early 1990s and the second half of the 2000s was a historical aberration and a multipolar environment is required to maintain global peace and stability. Similarly, Russian and Chinese leaders share the view that both Russia and China are entitled to have geopolitical influence in their neighbourhoods as well as curbing American penetration into their regions. A common view shared by both countries is that Western claims to universal human rights and morality are wrong and should they be pursued at the barrel of a gun the end result would be global instability and war.

From the perspectives of both countries, nations have different conceptualizations of morality, human rights and political legitimacy due to their peculiar historical experiences, geographical locations, state-society traditions and human capital. Looking from this perspective Russia and China are now the most ardent supporters of the idea that non-involvement in states’ internal affairs and the recognition of their national sovereignty should remain as the most sacrosanct values of international relations. Therefore, Western attempts to promote democracy abroad are not legitimate and the principle of responsibility to protect masks imperialistic desires to impose one’s values onto other. Likewise, there are no universally recognized standards to define humanitarian interventions and nation-building initiatives in war-torn countries.

Common values

Russian and Chinese societies are inclined to legitimize strong state authority over society. The post-modern values of consumerism, hedonism and extreme individualism in liberal democratic Western societies are considered to be vices to be avoided. Both countries are ruled by strong charismatic leaders and the scope of civil society participation in national politics is strictly limited. Martial values are strong within Russian and Chinese societies and the value of individuals emanate from their contribution to the well-being of their societies and security of their states.

Even though the scope of cooperation between Russia and China has recently widened to encompass many different realms, it would be wrong to characterize the current relationship as one of alliance. It is more a growing strategic partnership of convenience than a NATO-like collective defence alliance. Both Presidents Putin and Jinping see each other as good friends and take pride in visiting each other more than 30 times since Xi Jinping came to power in 2013. China is Russia’s number one trading partner and the volume of bilateral trade is a little more than $100 billion. Yet, Russia is not among China’s top trade partners. Russia mainly sells China oil and gas whereas China exports to Russia predominantly manufactured merchandise goods. The Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union and Chinese-led BRI have merged with each other as parts of the Greater Eurasian Economic Partnership.

Both countries are the two most powerful members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and the so-called BRICS community. Their military cooperation is also noteworthy. Russia is the number one arms exporter to China and Chinese military modernization has been made possible, among other things, by Russian technology transfers. Both countries organize joint military exercises in different locations across the globe. Their diplomatic cooperation within the United Nations and other international settings is also remarkable.

However, it is still the case that both countries define their relations with the United States as more vital to their security and economic interests than their own bilateral relations. It seems that neither Russia nor China would accord the other the big brother role in an emerging alliance relationship. Indeed, both countries take great pain to avoid giving the signal that their goal is to help establish a NATO-like military alliance.

Building blocks of Russia-China Relationship

There are several building blocks of the contemporary Russian-Chinese relationship: (a) opposition towards the US and its policies; (b) substantial bilateral cooperation in energy, economy, security and defence realms; (c) domestic political concerns of similar kind; (d) dissatisfaction with the normative framework underpinning the US-led liberal international order.

Without a doubt, shared animosity towards US primacy in international politics and dissatisfaction with particular US policies, such as the missile defence deployment, have served as the glue that binds Sino-Russian relations in the 21st century. Both states regard the US as limiting their freedom of action in international politics and use bilateral cooperation, specifically in the UN Security Council, to balance the US. Close ties make it difficult for Washington to isolate either Russia or China politically. It would be a mistake, however, to reduce Sino-Russian relations to anti-Americanism.

For the last decade, both states developed substantial bilateral ties, in particular in energy, economic, security and defence realms. Joint military exercises became a routine, with annual naval drills (Joint Sea) and regular land exercises (Peace Mission). Russian arms sales revived and recently included Su-35 fighter jets and S-400 anti-missile systems. Moreover, the People’s Liberation Army, PLA, for the first time received equally advanced technology as their Indian counterpart, previously privileged by Moscow. The PLA’s participation in the Vostok-2018 Russian exercises did not only send a strong political signal, but also demonstrated legal and logistical improvements in mil-to-mil cooperation.

Energy ties constitute a particularly important element of Sino-Russian cooperation due to the important place energy occupies in Russia’s domestic political system and its foreign policy. China has emerged as Russia’s number one partner in that realm. In the course of the last decade, Beijing provided key Russian state (Rosneft, Transeft) and private (Novatek) companies with several dozen billions of dollars in loans and prepayments. China thereby contributed substantially to strengthening the pillars of Putin’s political-economic system.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.