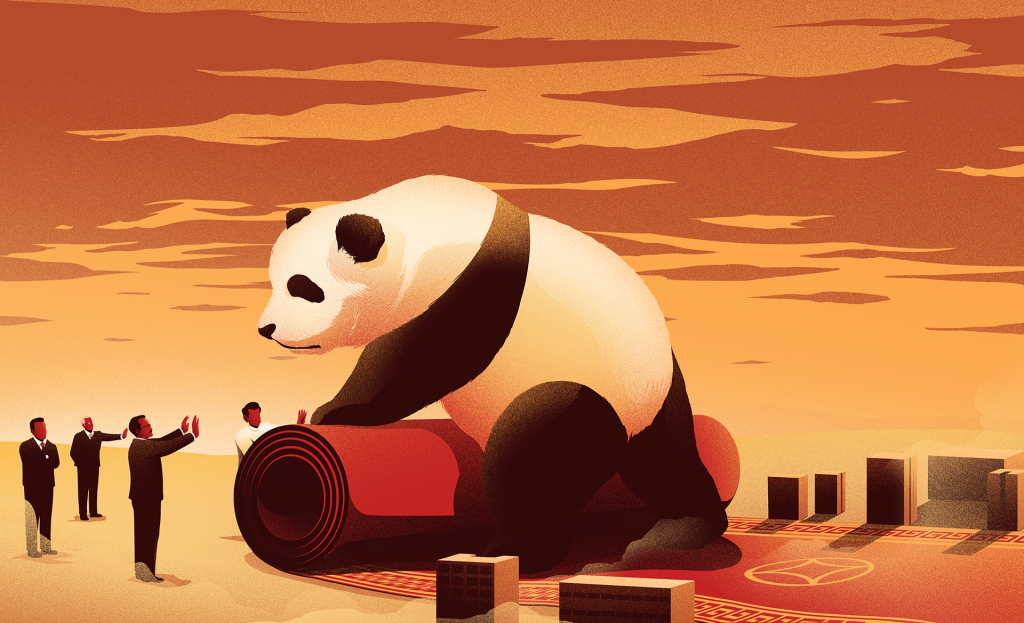

China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Debt Trap or Soft Power Catalyst?

Shafqat Javed

China is a powerful international actor as the world’s most populous country and its second-largest economy. The country also invests significantly in modernizing its military. With signs that the United States will retreat from a leadership role under the Trump administration, China has positioned itself as a champion of globalization and economic integration, perhaps signalling a desire to step in as a greater international leader. It is doing this by doubling down on soft power, a measure of a country’s international attractiveness and its ability to influence other countries and publics. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been described as a vehicle for soft power as it calls for spurring regional connectivity. However, as China’s trade scope spreads across the world through the BRI, so do concerns about the predatory style the country has embraced in dealing with its trade partners. This raises a million-dollar question: is the BRI a debt trap or is it a catalyst for its soft power? Let’s find out the answer.

Six years since Chinese President Xi Jinping launched the New Silk Road infrastructure project called Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – a labyrinth of overland corridors and shipping lanes that make up a maritime road meant to connect Asia with Africa and Europe – most of the developing countries are welcoming the idea as a plausible option to expand roads, railways, ports, and other key infrastructural projects due to the low-interest credit facilities offered by the Chinese and minimum or, in some cases, no strings attached, which contrasts grants and aid from the West. Some schools of thought have even hailed the BRI as the 21st century Marshall Plan that offers an opportunity to cut trade costs, boost connectivity, and reduce poverty in most of these developing countries. Many argue that this colossal endeavour could make or break China’s future, at least from a foreign policy perspective, but domestic scepticism seems to be already present. The stakes are high, and the attention that this project has been receiving drew visionary praise as much as harsh criticism and dismissal.

Beyond China’s actions and the world’s response, the objective of the Belt and Road Initiative seems to have evolved. From a more economic-oriented goal of facilitating export of China’s excess capacity through increased trade connectivity, it has become a soft power tool with a large part of the infrastructure projects considered strategic. The increasingly broad objective of President’s Xi’s global plan has attracted the attention not only from the BRI members, but also from other major players such as the United States and the European Union.

It is a ‘debt trap’

The number of articles mentioning this concept in relation to China’s foreign policy, as much as the effects in the receiving countries, has skyrocketed in the past few years. At first, most articles might have originated from the so-called ‘Western media’. Yet the trend quickly caught the attention of countries involved in the BRI. An often-cited example of the ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ is the case of Hambantota in Sri Lanka, where the local government signed the port away on a 99-year lease after it failed to repay Chinese loans.

More recently, due to growing international pressure, China attempted to address this concern and accusation in multiple ways. First, in the national media, then Xi Jinping reached directly to global leaders, and later also through the official Second Belt and Road Forum in July 2019. One of the most recent developments corroborated the fears of a debt trap, but with a twist: China could eventually be the one facing the consequences of this growing debt, instead of some less powerful countries that embraced the initiative. More precisely, the ‘obsolescing bargain model’ in which the more China invests in a host country, the less bargaining power, and hence demands for renegotiation, will increase. Eventually, this will reduce the already limited prospects of profitability. While this whole project is still slowly unravelling and it may be too early to draw hastily conclusions, there are already a few instances which can exemplify the many difficulties experienced by China, but also the willingness from the receiving parties to make it work.

The examples are mostly located in Southeast Asia but more can probably be found in Africa as much as in Latin America and some parts of Europe and beyond. Although it has been argued that ‘democracies are turning against’ the BRI, at least a few Southeast Asian ‘flawed’ democracies are showing positive outcomes, but not without controversies.

Although most critics try to observe how the BRI is received by broader audiences, beyond the sole government and the elites who are likely to have strong economic interests in the projects, what about the opinion of people who might indirectly benefit from increased connectivity and people-to-people interaction, or even suffer from the intervening dynamics brought by this influx of investments and infrastructure? Even though several Southeast Asian countries are ruled by assertive ‘strongmen’, common citizens could still have a say in how their country should deal with this neighbouring juggernaut. For instance, some anti-China movements are becoming more vocal. The actions of a country and how they are interpreted and received by the receiving audience could result in a better image, an attractive and legitimate one. These perceptions could gradually improve the overall reputation and, in turn, create goodwill towards even greater collaboration and stronger bilateral relations. When non-coercive methods are implemented, as opposed to the use of force and bribery, soft power is at work.

One topical case involved is of Mahathir Bin Mohamad, Malaysia’s prime minister. While several observers immediately picked up Mahathir’s warnings on a “new version of colonialism” as a clear opposition to the BRI and China, he promptly rejected these speculations, expressing instead support to the initiative. In April 2019, the stalled mega-projects were eventually renegotiated and expected to resume soon after, and additional ones were being considered. However, the leader’s view might not be reflected by common citizens.

In January 2019, the ASEAN Studies Centre at ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute published The State of Southeast Asia: 2019 Survey Report. In the report, Southeast Asian experts ranging from political scientists and media pundits to businesspeople were invited to express their opinions towards several matters affecting the region. One question asked: “What is your perception of the Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)?” Almost one third of the respondents believed that the BRI “will benefit regional economic development and enhance ASEAN-China relations”. 35% acknowledged that the BRI will fulfil the “needed infrastructure funding for countries in the region”. Almost 50% recognized that ASEAN countries will be brought closer to China’s orbit, or sphere of influence. Only 16% did not see any major advantage brought by the initiative claiming that it “will not succeed as most of its projects provide little benefit to local communities”. Another questions asked: “In light of the experiences in Sri Lanka (Hambantota Port) and Malaysia (East Coast Rail Link), what is your view of BRI proposals in your country?” 70% of the respondents demanded caution to their respective governments when negotiating with China. Just below 25% expressed a positive or somehow positive view, while 6.6% believed that the avoidance of any BRI involvement was the right path. Within ASEAN, the countries with more favourable views were Brunei Darussalam and Laos, followed by Cambodia. The country with the least favourable views was Malaysia. Even in this case, the opinion of experts in the field may not reflect the one of the broader population but, in the case of Malaysia, it is already fairly distant from the one of their political leader. Yet it should be noted that this survey was conducted before April’s renegotiation of the Malaysian mega-projects.

One more report from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), published in mid-2019, covered more granularly the several aspects to be considered when assessing the BRI in Indonesia. The main focus was the interaction between strategic and economic issues, but the socio-cultural aspect was also considered when addressing the influx of foreign workers from China, and how this can affect the local population.

It is ‘Soft Power’

As mentioned earlier, China is aspiring to become a global leader by doubling down on soft power. is attempting to export its approach to development, which has lifted hundreds of millions of its people out of poverty. The Belt and Road Initiative, or BRI, described by leaders as a vehicle for soft power, calls for spurring regional connectivity. It seeks to bring together the Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road through a vast network of railways, roads, pipelines, ports, and telecommunications infrastructure that will promote economic integration from China, through Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, to Europe and beyond. To finance a share of these international projects, China contributed $50 billion to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank upon its founding, half of the bank’s initial capital. Beijing also pledged $40 billion for its Silk Road Fund, $25 billion for the Maritime Silk Road, and another $41 billion to the New Development Bank (established by BRICS states: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa).

Separately, Beijing has also implemented aid programs that do not conform to international development assistance standards: its aid typically focuses on South-South partnerships in the developing world; comes without conditionality; is predominantly bilateral; and includes not only grants and interest-free and concessional loans, but also other forms of official government funding. A number of training programs have supported public health, agriculture, and governance.

That said, there seems to be a limited amount of research covering the relation and mutual influence between soft and economic power. While the ongoing trade war between the US and China is drawing the attention to hard power struggles, China and most ASEAN countries are still striving to fuel their growth in the hope to evade major concerns such as the middle-income trap. Collaboration between these countries is likely to be supported by ‘soft strategies’ to improve the national image and reputation, which could eventually result in tangible economic benefits and long-term cooperation.

There is little doubt that the Chinese market and its economic might can be ignored, but it is equally unlikely that Southeast Asian populations will all bend to the will of their powerful neighbour. If China truly believes in a win-win scenario, a ‘peaceful development’, greater efforts in developing soft power through attractive features and legitimate actions across the region (and beyond) are necessary. For instance, the idea of connecting physically –through infrastructure– and socioculturally –through people-to-people interaction– ought to be implemented in a concerted and coherent manner to avoid overall resentment and fears such as locals’ feeling of being ignored, if not exploited. Similarly, in another blog post from Bruegel, the authors argue that the “worsening image of BRI is definitely a wake-up call for China in its pursuit of a successful strategy to increase soft power globally”. The post also corroborates part of my reasoning about the connection between soft and economic power when claiming that “[f]rom a more economic-oriented goal of facilitating export of China’s excess capacity through increased trade connectivity, [the BRI] has become a soft power tool with a large part of the infrastructure projects considered strategic”.

China – A Model for Peaceful Development

China proposed the “Belt and Road Initiative” to connect the world and bring all nations closer, to have further trade and cultural exchanges, and to build an economically strong and moderately prosperous society. In other words, China’s two productive packages namely “Building a community with shared future for mankind” and “Belt and Road Initiative” are likely to mitigate the ongoing challenges to a great extent.

For constructing a violence-free and peaceful community with shared future for mankind, all nations need to seek common ground, urge concerted global efforts to promote the spirit of brotherhood, take new approach to develop state-to-state relation with communication rather than confrontation and settle dispute through dialogue.

China seeks to form a prosperous society and freedom from want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the ruling party. The blueprint for poverty alleviation has been highly fruitful and it will bear the desired result in 2020. Achieving a prosperous life, the Chinese will enjoy the fruit of socialism with Chinese characteristics and reap the benefits of reform and opening-up began four decades ago.

Meanwhile, China urges all nations to open their doors wider so as to reinforce trade, strengthen cultural bonds and people-to-people exchanges, and share their will and woes. Indeed, no individual or nation can be great if it does not have a concern for others. China, which is one of the largest contributors to the global economy, is ready to share the fruit of its reform and opening-up with the world.

It is self-explanatory that peace, development and win-win cooperation have been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of all peoples. That is to say, all members of the human family seek to live a free, peaceful and prosperous life and exercise their inherent rights and liberties without obstacles. This all dream will come true if the world zeroes in on the construction of building a community of shared future.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.