Water Scarcity in Pakistan.

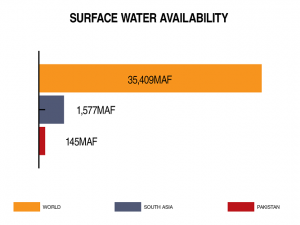

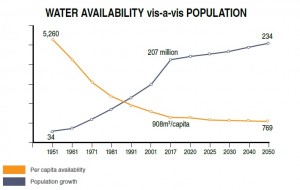

Pakistan is, currently, mired in several multifarious crises, but one of the most pressing issues that the country faces at the moment is the water crisis. Pakistan faces a serious water crisis as per-capita water availability falls due to diminishing freshwater supplies and the exponentially increasing demands of the country’s burgeoning population. According to the National Annual Plan 2019-20, during the last 71 years, the per-capita availability of water in the country has come down to an alarming level of 935 cubic metres from 5,260 cubic metres. If an effective water-storage strategy is not adopted, the per-capita water availability in the country would decrease to 860 cubic metres by the year 2025. It would further lower to 500 cubic metres by 2040, if measures are not taken to conserve water in the country. If the water crisis in Pakistan is not solved, the impact felt by people in the country will worsen.

Pakistan is grappling with many serious challenges – some political, some physical and some mix of both. Of these, the least-talked-about, yet a key existential challenge is ‘water scarcity’ as it has direct bearing on food security as we have a population of almost 208 million to feed. Water crisis is becoming critical for Pakistan. Most people do not know that Pakistan crossed the “water stress line” in 1990 and the “water scarcity line” in 2005. According to experts, if we don’t act now to combat this situation, we may run out of water by 2025.

Pakistan is predominantly an agrarian country, with most of the economy dependent on water to grow crops. Agriculture contributes around 19% to the country’s GDP, and is by far the largest user of water. Almost 90% of the available water, including both surface and groundwater, is used in agriculture for irrigation. We claim to have one of the best and largest irrigation systems in the world; however, Pakistan is a water-scarce country now, where per-capita water availability has dropped to almost 1,000 cubic metres. Consequently, it has put our food security at risk because an overwhelming majority of our food comes from agriculture. Agriculture is already under stress to meet the food demand of the fast-growing Pakistani population. If history is anything to go by, the situation is expected to get increasingly worse with serious implications for food security and our existence.

The sustainability of water resources is a challenge in Pakistan and a consequence of multiple factors: mismanagement of water resources, inadequate storage facilities, low water-use efficiency (WUE), water wastage, inappropriate cropping patterns and outdated water pricing mechanism.

Pakistan has one of the lowest per-capita water-storage capacities in the world. The country has per-capita water- storage capacity of 121 cubic metres that is equal to Ethiopia’s. Unlike Pakistan, USA and China have per-capita storage of over 2,000 cubic metres. Even India, our next-door neighbour, despite being seven times more populous than us, has per- capita storage capacity of over 200 cubic metres. Storage of our major national reservoirs caters for only 10% of annual inflow, against the world average of 40%.

Consequently, water- storage capacity has decreased to less than 30 days against the minimum requirement of 120 days (Development Advocate Pakistan, Issue 4, UNDP).

What is Causing the Water Crisis in Pakistan?

Population Increase

Pakistan is the fifth-largest country in the world with more than 220 million people. By 2025, Pakistan’s water demand could reach 274 million acre-feet (MAF) while the supply of water could remain at 191 MAF. Rapid growth of population has reduced annual water availability per person which is huge challenge for country. Related to this, urbanization is also paramount reason behind water crisis, as, requirement of water in urban areas is more compare to rural areas owing to commercial and industrial purposes. Therefore in most crowded cities, availability of water has become a grave issue which is not addressed by Pakistani government.

Agriculture

The commonly-grown crops in the country are highly dependent on water. The country grows rice, wheat, cotton and sugarcane. Crops like these are responsible for 95 percent of the country’s water use. Poor water management in Pakistan is causing high water waste within the agriculture sector. Pakistan has an inefficient irrigation system that causes a 60 percent water loss. In addition, Pakistan has low water productivity in comparison with other countries. Water productivity is “the physical or economic output per unit of water application.” Pakistan uses a lot more water to produce crops than in other countries.

Climate Change

Pakistan gets its water from rainfall and rivers, as well as snow and glacier melt. Because the rain is seasonal and 92 percent of the country is semi-arid, Pakistan is dependent on the rain for its water supply. Pakistan is facing an increasing demand for food while it is experiencing a reduction in the water supply. One of the reasons why Pakistan will face an increase in water demand could be climate change, which could effect an increase in the demand for water for crops. Climate change could cause water in the soil to evaporate faster, which could increase the demand for water.

Lack of Storage Facilities

This situation of water scarcity has arisen owing to outdated water-storage system and mismanagement of water resources by the government. No big dams have been built in recent years to store water. Tarbela and Mangla dams are the only big dams in Pakistan which can store floodwater. By 2018, both had reached their “dead” levels, meaning that they do not have enough water to operate. Moreover, deficiency of small dams and reservoirs results in wastage of rain water.

Desperate times call for desperate measures; we need to build multipurpose dams in the country, so that we can withstand floods, droughts and store excess water from melting glaciers and runoff from monsoon. Simultaneously, we need to strengthen the existing reservoirs.

Pakistan’s water resources are confronted with conflicts. Distribution of water among different federating units has been a problem since 1947. Inter- provincial accord of 1991, known as Water Apportionment Accord of 1991, has failed to fix it. Indus River System Authority (IRSA) has failed to implement the Accord according to its letter and spirit due to the lack of trust among provinces that arises because of many reasons: absence of irrigation infrastructure in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Balochistan, Accord’s weak framework, lack of accurate and real-time measurement of water, etc. Policies that promote data secrecy impede the effectiveness of institutions that are tasked with planning and allocation of resources. Opacity creates an atmosphere of mistrust. Lack of trust and scarcity of resources will ensue in more competition and conflicts among all stakeholders.

We need to build the capacity of the federal and provincial institutions responsible for water data management. They perform complex and interdependent functions of modelling, forecasting, water-monitoring, distribution and use. Federal legal mandate should be clarified for collection and sharing of water information. In addition to that, measures should be taken to strengthen the provincial regulatory frameworks for access of groundwater and for its management and regulation. National Water Policy 2018 has proposed measures to establish a National Water Council to provide essential support for cross-jurisdiction basin planning. It is imperative to establish an implementation framework for National Water Policy that articulates roles, time frames and process for basin planning.

Pakistan has one of the largest irrigation networks in the world, covering over 17 million hectares and registering losses of over 60% of irrigation water (Pakistan Academy of Sciences, Islamabad). Water courses, flood irrigation system, canals, and distributary channels are few of the major channels that cause most water losses. The percentage of non-revenue water (NRW), for which no price is charged, is around 45-50% as compared to the world’s average of 10-15%.

Whilst not compromising on the efforts to augment the storage and supply, we need to also focus on better management of available water. Conventional approach of ‘Build-neglect-rebuild’ is neither sustainable nor efficient and causes annual loss worth 11 billion dollars of assets in irrigation infrastructure according to a study of the World Bank. Water courses should be improved to minimize seepages, leakages and other losses. Simultaneously, we need to adopt the appropriate sowing methods including bed-plantation and direct seeded rice (DSR). Water-saving techniques such as raised beds, drip irrigation and rain guns should be encouraged. The Punjab agriculture department has provided subsidies worth billions of rupees on installation of drip system on shared basis to hundreds of thousands of farmers; however, its use is still seen as an exception than rule. Need of the hour is to scale up this initiative to all such areas where it is commercially feasible.

As per a study published by Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, Pakistan has one of the lowest water- use efficiency (WUE) when it comes to a crop yield per hectare. In case of wheat, it stands at 0.5kg/cubic metre compared with 1kg/cubic metre in India. Similarly, Pakistan gets 2.5 tons/hectare wheat against the India’s average of 3.5 tons/hectares despite having similar climate and land characteristics. WUE should be improved by at least 25% to increase efficiency.

Did you know?

- According to international standards, a country must have 1,800 cubic metres of water per person, per year, while a level below than 1,000 cubic metres means that a country faces shortage of water.

- According to the Falkenmark Water Stress Indicator:

- A country with less than 1700m3 per-capita water resources is “water-stressed”

- If the per capita resources are less than 1000m3, it is facing “water scarcity”

- If water resources per capita fall below 500m3 per person, the country is suffering from “absolute water scarcity”.

- Only 36% Pakistanis have access to safe drinking water and 21 million people have to travel long distances to get water.

- Pakistan is ranked 23rd out of 167 countries in the world which face water scarcity.

- 5. A country needs to have forests on 25% of its total land in order to avoid the negative impacts of climate change.

- According to the Pakistan Forest Institute, the country has only 5.01% forest cover and 27,000 hectares of area is being lost annually due to the cutting of trees.

- Based upon data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites collected between 2003 and 2013, the Indus Basin aquifer in Pakistan and India is the most overstressed in the world, second only to the Arabian Aquifer System.

- A 2015 IMF report projects that water demand will reach 274 MAF by 2025 whereas the supply will remain unchanged at 191 MAF. Approximately, 83% of a demand-supply gap will be witnessed, as a result.

- On 24 April 2018, Pakistan’s Council of Common Interests unanimously approved the country’s first-ever National Water Policy (NWP). Following the meeting, the Prime Minister and four Chief Ministers signed the Pakistan Water Charter, pledging commitment to the NWP.

- A substantial part of Pakistan’s freshwater resources is generated from outside the country. Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), signed in 1960, provides a mechanism for sharing of water of Indus system of rivers with India.

The state agencies responsible for water management lack the capacity and have no-to-limited knowledge about the current best practices. We need to improve the capacity of the institutions that are responsible for recording, monitoring and analysis of groundwater data. Instead of billing the irrigation tariff to the farmer at a cost that is contrary to reality, we need to reform the irrigation tariffs according to the realistic operational and maintenance costs. We should employ advance data techniques to record the actual consumption. It would enable us to charge a consumer in proportion to his actual consumption and would force water conservation.

A latest report of the Federal Commission on Agriculture tells us that water- loving crops are getting increasing share of the total cultivated area. Rice and sugarcane top the water-consumption chart. It takes an unbelievably high quantity of 3,000 litres and 1,500 litres of water to produce one kilogram of rice and sugar, respectively. Ironically, they are being cultivated on more and more area. This time, rice was cultivated on more than 3.3 million hectares. This large, scale shift to rice, even in the areas where groundwater resources are already under stress, for instance district Sanghar in Sindh, has put intense pressure on groundwater reservoirs being depleted at an alarming rate.

It would require coordinated and concentrated efforts to discipline the unchecked growth of water-loving crops. Firstly, we should map areas which have enough water to support the cultivation of water- loving crops. Secondly, water-loving crops should be replaced with edible oil crops that need one-tenth of the water than rice and sugarcane in the areas where rice is being currently cultivated and level of underground water has gone to historic low. Local production of edible oil will reduce our import bill and save billions of rupees of water too because we actually export water when we dispatch rice to other countries.

We have witnessed mushroom growth of tube-wells across the country that are major cause of ground-water depletion. Nearly 65% of the water used for irrigation purposes is pumped through tube-wells. A policy should be devised to regulate the installation and operation of tube-wells for minimizing the excessive extraction of groundwater.

We are running against time. The country’s water challenges must be addressed on emergency basis to protect climate, economy and life. It is a real and existential crisis and needs a befitting and conscious response.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.