Political Genius of Quaid-i-Azam

Prof. Sharif Al-Mujahid

“Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation state. Muhammad Ali Jinnah did all three”.

— Stanley Wolpert

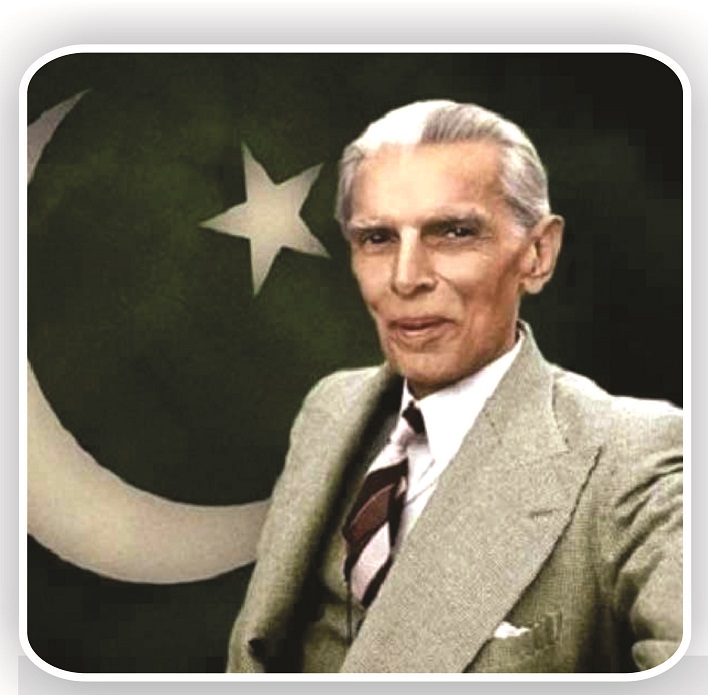

Mohammad Ali Jinnah Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the outstanding leader and a visionary statesman created this nation state of Pakistan by legal and constitutional means, with the power of the pen, speech and vote. Being endowed with qualities, such as a heart fired up by great fervour and sincerity, a clear vision and intellect, Jinnah was destined to play a prominent part in politics. In the words of Raja Sahib of Mehmoodabad, “He [Quaid-i-Azam] is our teacher, preceptor and guide – that is how we of the younger generation regard our great Quaid. He received our allegiance and, having received it, taught us what true and honest politics is; and has guided us on the right political path. He has steered our mind clear of pseudo-nationalism to a right perception of the implications of that patriotism for the Indian Muslim which, while not forgetting the true interests of the Motherland, holds fast to Islam; and above all he has, by making it his own by the clarity of his exposition and the irrefutability of his arguments, given an irresistible momentum to that life-giving movement – the movement for the creation of sovereign Muslim States in those parts of India where Islam pervades i.e. Eastern and North Western India. May he live long to see the consummation of this inspiring ideal.”

In one respect, the epoch that ended with the birth of two nations on August 14-15, 1947, in South Asia, was the most remarkable in Indian history. It had produced an almost incredible galaxy of eminent thinkers, distinguished politicians, dynamic leaders. Some of these were leaders of rare calibre, born but in centuries. Political giants by any definition, they were, in their life and work and setting, comparable to some of the greatest names in modern history; Washington, Bismarck, Cavour, Lenin, Ataturk.

Great as these leaders were as politicians, legislators, freedom fighters or as mass leaders holding charismatic authority over countless millions, the one leader who combined in himself multi-dimensional roles in various phases of his long, chequered career, was Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Great and many were the roles that Jinnah was called upon to fill in. So were his achievements.

Great as these leaders were as politicians, legislators, freedom fighters or as mass leaders holding charismatic authority over countless millions, the one leader who combined in himself multi-dimensional roles in various phases of his long, chequered career, was Quaid-i-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Great and many were the roles that Jinnah was called upon to fill in. So were his achievements.

In his early life, he was a distinguished member of the Bar. In 1910, he became a member of the newly constituted Imperial Legislative Council. At one of its first meetings, he clashed with Lord Minto, the Viceroy, over the treatment of Indians in South Africa. He was also the first Indian to get a Private member’s Bill on the Statute Book.

Jinnah, who was associated with this Council and its successor, the Central Legislative Assembly, for some thirty years, soon became the leader of a party inside the legislature and one of its most influential members. Montague, at one time the Secretary of State for India, considered Jinnah “perfect mannered, impressive looking, armed to the teeth with dialectics.” Jinnah, he remarked “is a very clever man, and it is of course an outrage that such a man should have no chance of running the affairs of his own country.”

For about two decades since his entry into politics (1904), Jinnah was a confirmed nationalist. (Gokhale had said of him, “He has true stuff in him and that freedom from all sectarian prejudice which will make him the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.”

And Jinnah lived up to that faith in him: he became the architect of Hindu-Muslim unity, having been the moving spirit behind the Congress-League Lucknow Pact (1916), the only pact ever contracted between the two organisations. No wonder, Sarojini Naidu waxes eloquent over “the remarkable breadth and boldness of his statesmanship, his consummate grasp of both the transitional phases and the abiding principles of political evolution…”

While Jinnah was readily recognised as an illustrious politician and a statesman of his age, few ever expected that he could “establish between himself and his people that instinctive and inviolable kinship that makes Muhammad Ali, for instance, a living hero of the Mussalmans and Mahatma Gandhi a living idol of the masses”. Yet when he took up the leadership of the united Muslim League in 1934, he showed how dynamic a mass leader he could be – if and when he chooses.

While Jinnah was readily recognised as an illustrious politician and a statesman of his age, few ever expected that he could “establish between himself and his people that instinctive and inviolable kinship that makes Muhammad Ali, for instance, a living hero of the Mussalmans and Mahatma Gandhi a living idol of the masses”. Yet when he took up the leadership of the united Muslim League in 1934, he showed how dynamic a mass leader he could be – if and when he chooses.

The degree of rapport that he established among Muslim masses, no one had ever done before. His popularity was such that a foreign observer Beverely Nichols could safely remark in 1942, “He can sway the battle this way or that as he chooses.

His one hundred million Muslims will march to the left, to the right, to the front, to the rear at his bidding and at nobody else…” In fact his popularity among the Muslims was matched, if at all, by Gandhi’s among the Hindus. No wonder, he became their Quaid-i-Azam – “the Greatest Leader”.

In 1917, Sarojini Naidu had hopefully remarked, “Perchance it is written in the book of the future that he whose fair ambition it is to become the Muslim Gokhale may in same glorious and terrible crisis of national struggle pass into immortality as the Mazzini of Indian liberation.“

That hope was squarely fulfilled but with this difference that the terrible crisis of the Indian national struggle turned him into the Mazzini of Muslim freedom.

This role, which represents the crowning achievement of his political career, he had donned in 1936 when he took up the leadership of the Muslims. The Muslims were then a crowd of disgruntled and disillusioned men and women. Neither the Muslims, much less the Muslim League which claimed to represent them, was a force to be reckoned with, so that Pandit Nehru thought he could conveniently write them off as a political entity. To make matters worse, divisive forces were ascendant and on the rampage.

In the face of such odds, Jinnah set about the task of uniting Muslims on one platform and under one flag. He had nothing to fall back upon except his unswerving faith in his own self and his people, his indomitable will, and the bold exhortations of a daring spirit whom the world knows as Iqbal.

And, yet, within three brief years he had awakened the listless Muslims to a new consciousness, organised them on one platform and under one flag, had given coherence to their innermost, yet vague, urges and aspirations.

But this was not all. He also filled them with his own indomitable will, his own faith in their destiny. From a mere rabble he made them into a nation, united, strong, self-conscious.

In fact, the metamorphosis the hundred million Indian Muslims underwent at his magic touch is simply incredible. From a confirmed minority, supplicating for paper safeguards in the future Indian dispensation, it became, within three years, a nation in its own right, a nation supremely conscious of its newly discovered nationhood, and a nation prepared to fight to the bitter end any attempt at cheating it of its high destiny.

No wonder, Muslim consciousness was stirred to a new pitch, and a hundred million people, under Jinnah’s inspiration, discovered their soul and destiny. They shed their minority complex and developed a national consciousness of their own. A Bismarck or a Cavour could not have done better – with all the armies they had commanded.

No wonder, Muslim consciousness was stirred to a new pitch, and a hundred million people, under Jinnah’s inspiration, discovered their soul and destiny. They shed their minority complex and developed a national consciousness of their own. A Bismarck or a Cavour could not have done better – with all the armies they had commanded.

In discovering the fact of separate Muslim nationhood, Jinnah had formulated the intellectual justification for launching the demand for a Muslim homeland in the subcontinent. This demand he formally launched in 1940. Interestingly though, as early as that he was confident that “no power on earth could prevent (the establishment of) Pakistan.”

Yet, as is well known to any student of history, there is many a hurdle between the perception of an idea and its realisation, between the launching of a movement and its consummation. And hurdles, almost insurmountable, he did of course encounter at almost every step.

To quote Dr Sachinanda Sinha, an otherwise bitter Indian critic, “No movement was more strenuously resisted both inside and outside India than was Jinnah’s demand for Pakistan. Its opponents were overwhelmingly influential and numerically so large, while its champions were few outside the League.

That, in spite of it, Pakistan had not only become an accomplished fact but (what is even more notable) had been accepted – albeit unwillingly – by the ‘Nationalists’ themselves, is a conclusive proof of Jinnah’s deep-rooted strength of conviction, indomitable courage, political tack and tenacity of purpose.”

And Jinnah had carried on the struggle, almost single-handedly – and, yet; won Pakistan. More creditable, however, is the fact that all through the bitter struggle, he never abandoned the constitutional path. A staunch believer in constitutionalism and in the evolutionary process, he never even for once called for violence and terrorism although it was a fashion with every mass leader in those days to invoke them.

Thus the Quaid founded a state without arms, without blood-baths, without an uprising, and through altogether peaceful methods.

And when Pakistan emerged in 1947, Jinnah stepped into the last great role of his career as the architect of Pakistan.

In spite of his failing health, he took upon himself the onerous duties of the head of the State, and set about the difficult task of consolidating it, and, moreover, securing its survival in uneasy, treacherous circumstances. Circumstances no other nation in the modern world was born into, or confronted with, says Professor Ralph Braibanti, former Director, Islamic and Arabic Development Studies, Duke University, South Corolina USA.

One wonders what would have become of Pakistan in those first, crucial twelve months had it not been for the steadying influence of this supreme leader who alone could wield the sort of authority he wielded, who alone could command the people’s allegiance in a measure he did.

One is, therefore, inclined to agree with Richard Symonds when he says, “He had worked himself to death, but had contributed more than any other man to Pakistan’s survival”. Similar sentiments were voiced by Lord Pethick Lawrence the last Secretary of State for India: “Gandhi died at the hands of an assassin; Jinnah died of his devotion to Pakistan”.

Great as Jinnah was as a leader of men, he was equally great as a master of situation, any situation. He had in him a rare combination of prescience, idealism, intellectual vigour, faith and resolution. Yet he was no visionary: he was pragmatic and down-to-earth all the time. These characteristics enabled him to see his chance clearly and unmistakably, and to seize it resolutely and unerringly.

He could rise to any occasion; he could crystallise a lifetime’s faith into one single bold action. In such bold action his political career abounds, and he was always known for his foresight and statesmanship in Indian political circles. And during the last two years of his life, Jinnah the statesman almost overshadowed Jinnah the politician.

Quotes about Quaid-i-Azam

Gandhi died by the hands of an assassin; Jinnah died by his devotion to Pakistan.

— Lord Pethick Lawrence

[He was] the originator of the dream that became Pakistan, architect of the State and father of the world’s largest Muslim nation. Mr. Jinnah was the recipient of a devotion and loyalty seldom accord to any man.

—Harry S Truman (Former US President)

Ali Jinnah is a constant source of inspiration for all those who are fighting against racial or group discrimination.’ (Nelson Mandela had come to Islamabad in 1995 and had insisted on including Karachi as a destination to visit Jinnah’s Grave and his house in Karachi where upon reaching he drove straight to the Quaid’s Mazar) At another occasion while addressing the ANC Mandela mentioned three names Ali Jinnah, Gandhi and Nehru as sources of inspiration for the movement against apartheid.’

— Nelson Mandela, (Former President of South Africa)

“If the Muslim League had 100 Gandhis and 200 Azads and Congress had only one Jinnah, then India would not have been divided!”

— Mrs. Vijay Lakshmi Pundit (A prominent figure and Jawaharlal Nehru’s sister)

There is no man or woman living who imputes anything against his honour or his honesty. He was the most upright person that I know, but throughout it all, he never, as far as I know, for one moment, attempted to deceive anybody, as to what he was aiming at or as to the means he attempted to adopt to get it.

— Sir Patrick Spen (Last Chief Justice of undivided India)

Quaid’s Quotable Quotes

“There are two powers in the world; one is the sword and the other is the pen. There is a great competition and rivalry between the two. There is a third power stronger than both, that of the women.”

“Expect the best, prepare for the worst.”

“Democracy is in the blood of the Muslims, who look upon complete equality of mankind, and believe in fraternity, equality, and liberty.”

“No nation can rise to the height of glory unless your women are side by side with you. We are victims of evil customs. It is a crime against humanity that our women are shut up within the four walls of the houses as prisoners. There is no sanction anywhere for the deplorable condition in which our women have to live.”

“You will have to make up for the smallness of your size by your courage and selfless devotion to duty, for it is not life that matters, but the courage, fortitude and determination you bring to it.”

“Do not forget that the armed forces are the servants of the people. You do not make national policy; it is we, the civilians, who decide these issues and it is your duty to carry out these tasks with which you are entrusted.”

“Islam expect every Muslim to do this duty, and if we realise our responsibility time will come soon when we shall justify ourselves worthy of a glorious past.”

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.