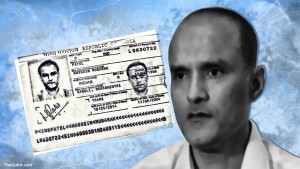

Kulbhushan Jadhav Case

and

Investigations in Terrorism Cases

Kamran Adil

- Introduction

In a research article titled ‘Is the International Court of Justice Biased?’ (2005), Professor Eric Posner of the University of Chicago noted about the International Court of Justice (ICJ), on the strength of ‘empirical evidence’, that:

- judges favour the states that appoint them;

- judges favour states whose wealth level is close to that of the their own states, and weaker evidence;

- judges favour states whose political system is similar to that of their own states; and

- (more weakly) judges favour states whose culture (language and religion) is similar to that of their own states.

The research was not the first and the last attack on the work of the ICJ that is as political as the United Nations (UN) itself. The fates of the UN and the ICJ are intertwined. The Statute of the ICJ is an annex of the Charter of the United Nations, and this legal annexation establishes an epistemological and ontological relationship between the two. Notwithstanding this integral interdependence, the work of the ICJ is perceived as a ‘dispute-settlement mechanism’ of the international legal system; the perception is often belied. In the Jadhav Case between India and Pakistan, which was finally decided on 17th of July 2019, the ICJ, once again reaffirmed the fact that it is as political as the UN. Avoiding the nationalistic and political binary analyses of the case, the instant write-up will present systemic issues that have not been addressed by the judgement rendered by the ICJ in the case; underlining the omissions will help draw lessons to map future trends of the working of the court.

- Systemic Omissions

Select ‘systemic omissions’ stated hereunder are based on the methodological approach of the ICJ in the case, and may be useful in informing on the way the cases have been ‘adjudicated’ by the ICJ:

- Facts not Established

The ICJ decided the case without establishing the facts. Paragraphs 20 to 32 deal with the factual background of the case. The judgement records, in paragraph 20, that the Parties (i.e. India and Pakistan) ‘disagree’ on several facts. The ‘disagreement’ has not been reconciled and without establishing facts, the ICJ applied the law. This ‘application’ of the law without clarifying the facts is a methodological problem with the ICJ. It is understood that all the facts cannot be clarified in an international ‘adjudication’ and neither is the ICJ a fact-finding court that could inquire into all the facts, but ‘essential facts’ should have been clearly established. In the instant case, the essential facts of India and Pakistan were diametrically opposing to each other’s narrative. While India alleged that Jadhav was ‘kidnapped’ from Iran, Pakistan’s claim was very straightforward that he was arrested from Balochistan (Pakistan). The factual controversy was not settled and the ICJ proceeded to apply law without deciding this ‘material essential fact’. Plain reading of the judgement shows that India practiced Carl Sandburg’s axiomatic quotation ‘if facts are against you, argue the law’.

- No Legal Weight to the UN Security Council Obligations

Pakistan, inter alia, rested its case on legal obligations emanating out of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373 (2001) that required cooperation between states for investigation of terrorism cases. Reminding India of this legal obligation, Pakistan, on 23rd of January 2017, requested the former to cooperate with it in investigating Jadhav. Instead of responding to this legal obligation, India filed its case in the ICJ on 8th of May 2017. The ICJ, in its judgement, noted the fact that Pakistan’s claim was based on the legal obligations related to the UNSC resolution. It, however, opted not to accord any legal weight to the UNSC resolution. The ‘systemic omission’ of not even considering the legal value of the resolution worth analysis has contributed in further weakening the institutional arrangements of the UN. In addition, the inference is that ‘no legal consequences’ flow for non-compliance of the UNSC resolution, and in future, it might mean that ‘sanctions’ related to the UNSC resolution may not enjoy the required level of legality.

Pakistan, inter alia, rested its case on legal obligations emanating out of the United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373 (2001) that required cooperation between states for investigation of terrorism cases. Reminding India of this legal obligation, Pakistan, on 23rd of January 2017, requested the former to cooperate with it in investigating Jadhav. Instead of responding to this legal obligation, India filed its case in the ICJ on 8th of May 2017. The ICJ, in its judgement, noted the fact that Pakistan’s claim was based on the legal obligations related to the UNSC resolution. It, however, opted not to accord any legal weight to the UNSC resolution. The ‘systemic omission’ of not even considering the legal value of the resolution worth analysis has contributed in further weakening the institutional arrangements of the UN. In addition, the inference is that ‘no legal consequences’ flow for non-compliance of the UNSC resolution, and in future, it might mean that ‘sanctions’ related to the UNSC resolution may not enjoy the required level of legality.

- Substituting Arbitration and Conciliation with Adjudication

The ICJ assumed the jurisdiction in the case by pressing into service Article 36(1) of the Statute of the ICJ and Article I of the Optional Protocol to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, 1961 (the Protocol). While Pakistan contested the assumption of the jurisdiction, it had argued that Articles II and III of the Protocol required sequencing i.e. referring to arbitration and reconciliation before resorting to ‘adjudication’ by the ICJ. The ICJ used its earlier judgement in the case of the US vs. Iran (1980) to find that cascading dispute settlement mechanisms of arbitration and conciliation could be substituted by the arbitration. The finding is interesting as it has potentially made Articles II and III of the Protocol redundant. This omission by the ICJ might result in narrowing down the choices for dispute settlement in the international legal order; more thought should have been given to the implications of such an approach.

- Criminal Investigation of Terrorism

In order to find truth in acrimonious environment, the role of criminal investigation cannot be overemphasized. The ICJ did not pay much heed to the law relating to international criminal investigations that could have been taken on a progressive tangent through the case. Pakistan averred that no cooperation was offered by India to further the criminal investigations in the matters related to Jadhav, but the court did not invest its time and energy to examine Pakistan’s point of view. Cooperation in criminal investigation would have opened new avenues and would have helped in settling ‘material essential facts’ that could, then, have been made the basis of applying the law related to consular access on solid foundations.

- Remedies

Last part of the judgement was devoted to ‘remedies’ (paragraphs 125 to 148). The ICJ noted that insofar as the remedies were concerned, ‘the choice of means is (sic) left to Pakistan’ (paragraph 146). In contrast to its established practice, the ICJ peeped into the nature of the review under Pakistan’s constitutional and municipal law by the help of Pakistan’s case law that has yet not availed finality. It embarked upon to discuss the scope of ‘review’ in the light of Abdul Rashid Case (Writ Petition No. 536/2018) decided by Peshawar High Court and stated that ‘the Government of Pakistan has appealed the decision and the case is still pending…’. Such reference to sub-judice matter within municipal law was unnecessary and reflected on the ‘belaboured’ approach of the ICJ in moving into unchartered waters. It went on to exhort Pakistan to ‘enact legislation’ (paragraph 146). In this overarching ingress into the national legal system of Pakistan, the ICJ omitted to call upon India to fulfil its legal obligations under the evolving international counter-terrorism law with special emphasis to cooperation in criminal investigation in terrorism cases and the state responsibility in dealing with such cases. The suggestion by the ICJ to Pakistan to ‘enact legislation’ in relation to a criminal matter, with retrospective effect, is not without implications. It is patently in violation of the general principles of criminal law as stated in Articles 22 (Nullum crimen sine lege—no crime without law) and 23 (Nulla poena sine lege—no penalty without law) of the Statute of the International Criminal Court.

- The Legacy of the Jadhav Case

Jadhav Case may be remembered for many things, but chiefly it will reflect on the not-so progressive interpretation by the ICJ, and for missing the opportunity of providing support and the much-needed legality to the processes related to criminal investigations in terrorism cases. The rule-based international legal order needs progressive interpretation by the ICJ for its growth; this progressive interpretation requires that the institutional mechanisms evolved by the residuary power of the international soft law be supported and acknowledged by international juristic bodies. In the instant case, the ICJ’s omissions have served the ideology of power than the idea of law.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.