Kashmir Conundrum and the International Law

Abdul Rasool Syed

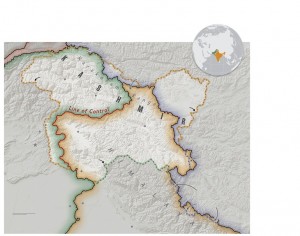

The scrapping of Article 370 and subsequent annexation and illegal occupation of the state of Jammu and Kashmir by India has, once again, brought into international limelight the seven-decade-old Kashmir issue, a prime cause of friction between two neighbouring nuclear states, i.e. India and Pakistan. Before this constitutional catastrophe, the occupied valley had special status, separate laws, constitution and flag. The Modi government has revoked this special status but the step is in utter contravention of UNSC resolutions and international law.

This mala-fide move by Modi government is indubitably aimed at eclipsing the importance of the Kashmir issue by localizing it, and putting it, thereby, on the backburner. However, the irrefutable fact is that the Kashmir is a disputed territory between India and Pakistan, and is recognized as such, without any reservation, by international community.

In the wake of the Indo-Pak partition, the princely states were given, under Article 2(4) of the Independence Act, a choice to join ‘either of the new Dominions’. While it was an easy decision for some states due to their geographical proximity, territorial contiguity or political and religious affiliation of the rulers and subjects, the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir was a complex issue that would later emerge as a conundrum and a nuclear flashpoint between India and Pakistan.

Sifting through the annals of history, one finds that in the beginning, Maharaja Hari Singh, the ruler of the Jammu and Kashmir state, toyed with the idea of remaining independent. However, Indian machinations spearheaded by Congress leaders including Nehru and Patel created such circumstances for Maharaja that he was left with no option but to capitulate to their demand of “Accession of state of Jammu and Kashmir to India”. Hence, Maharaja, due to unwarranted conditions forged by the Indian Machiavellian masterminds, had to agree to sign the instrument of accession to this effect. Thus, on October 27, 1947, the then-Governor-General of India, Lord Mountbatten, approved the accession with the condition that “as soon as law and order have been restored in Kashmir … the question of the State’s accession should be settled by a reference to the people.”

The purported Instrument of Accession (which India has so far failed to produce) denies the authority of any unilateral action by India. The terms of this Instrument would not be varied by any amendment to the Indian Independence Act, 1947, without acceptance of the ruler of the state (Clause 5). Further, nothing in the Instrument could have been deemed to be a commitment as to the acceptance of any future constitution of India, and nothing could affect the sovereignty of the Maharaja over the state (Clauses 7 and 8).

Insofar as the internationalization of the Kashmir issue is concerned, it is India that took the issue to international forum by knocking at the door of the UN Security Council back in 1948. Resultantly, the UNSC, via its Resolution 38, called upon the contending governments to refrain from aggravating the circumstances, and report any material changes on the ground. Thereafter, the Council issued, over a number of years, a total of 17 resolutions on the disputed status of Kashmir. UNSCR 47 of 1948, the most important of all resolutions on Kashmir, calls for the resolution of the dispute of Kashmir’s accession to either India or Pakistan through effecting the democratic means of a free and impartial plebiscite.

Simla agreement is another worth-quoting document, as its deemed as the premier bilateral accord between the warring nations. It holds that “principles and purposes of the Charter of the United Nations shall govern the relations between the countries,” hence shining light on the validity of the UNSC resolutions on Kashmir. The disputed nature of the issue is further reiterated as: “In Jammu and Kashmir, the Line of Control resulting from the cease-fire of December 17, 1971, shall be respected by both sides without prejudice to the recognized position of either side.

Moreover, the same Simla Agreement also forbids unilateral action to change the status of the occupied state. Clause 1(ii) of the agreement specifically states that neither side shall unilaterally alter the situation. Clause 6 further emphasizes that both the countries should discuss modalities for a final settlement of the issue through diplomatic means. Thus, India’s claim that the revocation of Occupied Kashmir’s ‘special status’ is its internal issue negates its commitments it made in the agreement.

Additionally, the right of self-determination is the basic principle of the United Nations charter and it has been reaffirmed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and applied countless times to the settlement of international issues. The concept played significant role in post-World War I settlement, leading, for example, to plebiscite in a number of disputed areas.

However, the establishment of UN in 1945 gave a new dimension to the principle of self-determination. It was made one of the objectives which the UN would seek to achieve, along with equal rights for all nations.

The principle of self-determination and the maintenance of international peace and security are inseparable. For example, the denial of this right to self-determination to the people of Kashmir has brought the two neighboring countries in South Asia—India and Pakistan to the brink of nuclear catastrophe.

Apart from the specific UN resolutions which guarantee Kashmiris the right to self-determination, the UN Charter in its Article 1(2) declared one of its purposes as, “To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples.” This serves as the biggest impetus to the said right under international law.

In 1952, the UN General Assembly further elaborated on this principle and stated in Resolution 637A(VII), that ‘the right of peoples and nations to self-determination is a prerequisite to the full enjoyment of all fundamental human rights’ and recommended that UN members ‘shall uphold the principle of self-determination of all peoples and nations’. The Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples enshrined in GA resolution 1514 of 1960 upheld the right to self-determination. The resolution explicitly says, “All peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”.

Moreover, the principle of self-determination was given protection in Article 1 of both the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). In 1966, these two covenants enshrined the self-determination principle verbatim as was laid in GA resolution 1514. The Declaration of Principles of International Law Concerning Friendly Relations (GA Resolution 2625 of 1970) went further in recognizing that peoples resisting forcible suppression of their claim to self-determination are entitled to seek and receive support in accordance with the purposes and principles of the Charter. Since the adoption of the Declaration in 1970, the ICJ has, on a number of occasions, confirmed that the principle of self-determination constitutes a binding norm of customary international law, and even a rule of jus cogens—peremptory rule of international law. Thus, international law and the specific UNSC resolutions on Kashmir uphold and provide the Kashmiris with the overriding principle of right to self-determination.

With the revocation of the state’s ‘special status’, the situation has now become an ‘occupation’ with an ‘unlawful annexation’. India is an Occupying Power and it has unlawfully annexed the state. From international legal opinion on the issue of self-determination, as developed in the aftermath of the Second World War and the process of decolonization, the fate of millions of people cannot be left to the whims of India. Given the UNGA resolution of 1960 concerning Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, the people of Jammu and Kashmir have every right to self-determination.

India has no title on the state under international law. India’s illegal occupation since 1947; denial of the right to self-determination of the people; application of India’s constitution by removing the state’s special status, make India an Occupying Power and its army a hostile force. The BJP’s recent attempt to include the territory of the state within the Union of India is an act of ‘occupation’ and ‘illegal annexation.

While commenting on Article 47 of the Geneva Convention IV, noted jurist Jean S. Pictet explains that the Occupying Power is the administrator of the territory and is under various positive obligations towards the Occupied Population (i.e. the Occupying Power cannot annex the Occupied Territory or change its political status). Jean elaborates that the Occupying Power must respect and maintain the political and other institutions of the Occupied Territory. Therefore, India being an Occupying Power cannot annex the state’s territory and is bound to keep the state’s institutions and territorial boundaries intact till the conduct of plebiscite under the UNSC resolution 1948.

The International Commission of Jurists has categorically stated that “the Indian government’s revocation of the autonomy and special status of Jammu and Kashmir violates the rights of representation and participation guaranteed to the people [of Jammu and Kashmir] under … international law”.

To cap it all, the world powers should take a leaf from the statement made on June 15, 1962, by American representative to the UN, Adlai Stevenson. He said, ”The best approach is to take for a point of departure the area of common ground which exists between the parties. I refer, of course, to the resolutions which were accepted by both parties and which in essence provide for demilitarization of the territory and a plebiscite whereby the population may freely decide the future status of Jammu and Kashmir.”

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.