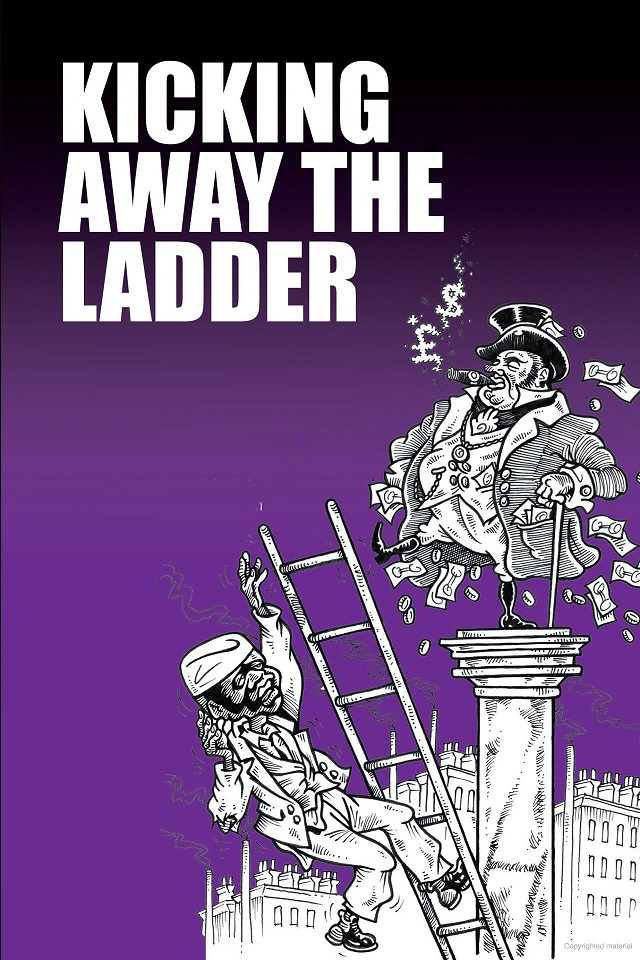

Kicking Away the Ladder

How did the rich countries really become rich?

Muhammad Shahid Rafique

There is currently great pressure on developing countries to adopt a set of “good policies” and “good institutions” … to foster their economic development. When some developing countries show reluctance in adopting them, the proponents of this recipe often find it difficult to understand these countries’ stupidity in not accepting such a tried and tested recipe for development.

After all, they argue, these are the policies and the institutions that the developed countries had used in the past in order to become rich. … However, curiously, even many of those who are skeptical of the applicability of these policies and institutions to the developing countries take it for granted that these were the policies and the institutions that were used by the developed countries when they themselves were developing nations. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, the historical fact is that the rich countries did not develop on the basis of the policies and the institutions that they now recommend to, and often force upon, the developing countries. Unfortunately, this fact is little known these days because the “official historians” of capitalism have been very successful in rewriting its history.”

This is how Ha-Joon Chang, a noted institutional economist, specializing in development economics and a Cambridge University Reader, starts his seminal book “Kicking Away the Ladder: Development Strategy In Historical Perspective” in which he has discussed how the now-developed countries became wealthy and what lessons this should provide for establishing a suitable framework for developing countries today. In this book, Chang takes stock of the factors responsible for the development of Britain and the United States of America. He analyses the history of capitalism in these two countries which he refers to as “unofficial” which is quite contrary to the commonly-held beliefs about capitalism. He mainly emphasizes that progress in the UK and the USA was heavily dependent on tariffs and protectionist policies, unlike the popular rhetoric of laissez faire. Now, they are dissuading the developing countries to do the same. Chang has examined the progress made by both these countries through the prism of tariffs and protectionism. This compels one to think whether it was tariff alone which triggered development in the countries or there were some other factors as well. The instant article intends to analyze the argument made by Chang in this book.

As noted earlier, Chang argues that the developed world now forces the developing world to do what they themselves had avoided when they were in this phase. Here comes the difference between the official and unofficial accounts of economic development under capitalism. Before proceeding to analyze the argument, we need to be sure-footed as to what is the difference, according to Chang, between official and unofficial accounts of capitalism. Official history of capitalism has it that economic development of USA and Britain is the outcome of laissez-faire trade policies. On the other hand, the developed countries aggressively used infant-industry protection policies when they were developing.

It is important to have import substitution defined at the outset. Import-substitution is a strategy by which infant-industry is protected by using locally manufactured goods. It is important to note that imports are banned and manufacturing is done for local consumption, not for export. The prime objective of import-substitution is to encourage and promote the growth of domestic industry. Export-promotion on the other hand is a policy to promote export by helping in export-related processed. Capital accumulation is defined as the process by which there is increase in the spread of capital through production. It is considered as one of the components of economic growth.

There is no denying the fact that Britain is the country to have extracted maximum benefit out of free trade. Its vast political expansion gave her advantage over others to engage other countries and colonies to engage in free trade. Treat of free trade or trade imposed upon a weaker state was what the Britain resorted to as a political tool for its expansion. It was in 1980s that the developing countries were compelled by the International Financial Institutions to draft their trade policies in consistent with Washington Consensus. Through international pressure, the developing countries adopted laissez-free trade policies. Such policy-measures taken by the developing countries were not without any trouble. Their infant-industries were open to fierce competition and could not grow. This situation was prevalent in most of the developing countries. They were not in a position as per structural adjustment programmes by the International Financial Institutions to protect their infant-industries by imposing tariff. This dilemma faced by the developing countries forced many economists to be skeptical about the effectiveness of laissez-faire trade policies. Chang argues that protectionist policies have been instrumental in the growth of both USA and UK. However it seems to be a highly debatable issue whether the imposition of tariffs was the sole factor responsible for the tremendous economic growth made by the capitalistic regimes. In the coming paragraphs, it will be investigated whether the protectionist policies are responsible for the growth as Chang argues or there are other factors which Chang has been oblivious of.

In the late 19th century it was witnessed that tariffs were positively correlated with growth in several countries including the UK. This is equally true in case of USA. During this period USA also resorted to protectionist policies thereby resulting in enormous growth. Arguably, motivation force behind the protectionist policies was to protect infant-industry. Chang’s main argument that the protectionist policies worked for these countries is credible to the extent that strong growth was witnessed whenever tariff was imposed.

A positive relationship between tariff and growth, however, does not establish a causal relationship. Some countries like Argentina and Canada, made good progress in the late 19th century. Importantly they were also high tariff states. It is noteworthy that economic strides made by them were not the outcome of import-substitution. Rather the development was the outcome of export expansion with increasingly robust domestic market. Import-substitution was not instrumental at all in case of Argentina and Canada.

It is interesting to note that there exists a strikingly positive relationship between growth and tariffs. The causes of this relationship need to be investigated minutely. When it comes to USA, it made tremendous progress in the late 19th century. It surpassed other countries in terms of economic growth during the period. A closer scrutiny will enable us to analyze the validity of Chang’s argument further. The economic growth of USA during the late 19th century when the protectionist policies were in place was primarily because of increasing population and capital accumulation thereof (Douglas A Irwin, 2001). However there has not been found a strong relationship between tariff and capital accumulation. Seen from this perspective, tariff does not seem to have influenced American growth during the period.

Before Chang wrote Kicking away the ladder, a lot of research had been conducted exploring the relationship between tariff and growth. However Chang does not make any mention of the research and completely sets aside other factors responsible for the growth. He has taken broader historical view into account and not used empirical data to support his argument. By doing this Chang makes otherwise an interesting argument unconvincing. Had he stayed more focused on exploring as to what extent the tariffs had played their role in growth, he would have made a meaningful contribution.

Tariffs were supposed to be instrumental in ensuring infant-industry protection in the late 19th century in America. The example of tinplate industry in America is perfect example of infant-industry protection. The industry did not make any progress until McKinley Tariff was imposed. After the imposition of tariff, it made remarkable progress. Before imposition of tariff the industry failed to develop because the price iron was too high which hampered the growth of the industry. Later on availability of iron at cheaper rates coupled with production experience turned around the industry. This would have happened even if there had been no tariff. From this example it can be inferred that tariff had its role in spurring the growth in America. But there were other equally important factors responsible for the growth and they cannot be set aside.

England has been a high tariff regime when it was developing. Indian textiles were banned because of superior quality and England resorted to import-substitution policy to protect its wool industry. Britain opened itself for free trade when it felt that it had got superiority over others. Chang’s main argument is credible that UK was never open for free trade. It protected its industry before exposing it to the fierce competition.

The developed countries adopted protectionist policies when they themselves were developing. However no strong relationship has been found between protectionism and growth. Though growth was witnessed when tariffs were in place, yet there were other factors instrumental for tremendous growth. Laissez-faire, on the other hand, has also created enormous difficulties for the developing countries recently. Despite all its drawbacks, liberalization in the world trade since 1945 has been on the rise. Chang however cautions the developing countries suggesting them to look at the history.

Overall, Chang gives a debatable and interesting argument about the history of capitalism in UK and USA. Instead of getting involved in numerical data, he refers back to history to substantiate his argument. He forces us to look afresh at history and draw lessons from it so that a suitable course of action may be chalked out for the developing countries. He cautions the developing countries not to be carried away by the mantra of liberalization of trade. Though Chang makes a fascinating argument, yet he should have come up with a solution for the developing countries in a world which is much different from the late nineteenth century.

The writer is a Chevening Scholar and has studied International Development: Development Management at the University of Manchester

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.