India-China Standoff

Dialogue is the only pragmatic option

Asif Khan Shinwari

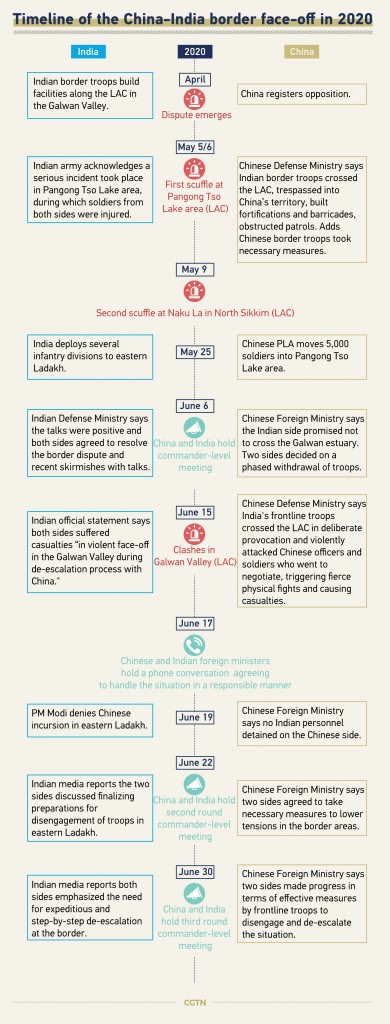

In the freezing heights of the Karakoram mountain range, a dangerous power play is unfolding. A military stand-off between India and China on their disputed border in the Himalayas has escalated into deadly clashes. The face-off in eastern Ladakh region, which was carved out of Indian-administered Kashmir last August, started on May 5 and May 6 when soldiers of both sides were involved in a skirmish. Indian officials say that Chinese troops had, within days, encroached on the Indian side of the demarcation line in the Ladakh region further to the west. India, too, has moved extra troops to positions opposite.

Although there are several reasons why tensions are rising now, competing strategic goals lie at the root, and both sides blame each other. India has built a new road in what experts consider the remotest and the most vulnerable area along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh. India’s decision to ramp up infrastructure seems to have infuriated China. The road could boost New Delhi’s capability to move men and materiel rapidly in case of a conflict. The infrastructure is aimed at narrowing the gap with China’s superior network of roads that it built years ago, but China is opposed to any Indian construction in the area, saying it is a disputed territory.

Although both sides have played down the incident, the military buildup in the sensitive region is ominous, given the emerging regional geopolitics. Recently declared a Union Territory by Indian authorities, separating it from the disputed state of Kashmir, Ladakh lies at the confluence of three nuclear states, i.e. India, China and Pakistan, and has a landlocked area of 50,000 square kilometres with a population around 300,000 people—46% Muslims, 40% Buddhists, and 12% Hindus. It is the area where physical military collusion between the armies of the two countries can take place, which makes it a potential flashpoint.

The India-China border conflict stretches back to at least 1914, when representatives from Britain, the Republic of China and Tibet gathered in Simla (now in India) to negotiate a treaty that would determine the status of Tibet and effectively settle the borders between China and British India. The Chinese, balking at proposed terms that would have allowed Tibet to be autonomous and remain under Chinese control, refused to sign the deal. But Britain and Tibet signed a treaty establishing what would be called the McMahon Line, named after a British colonial official, Henry McMahon, who proposed the border. India maintains that the McMahon Line, a 550-mile frontier that extends through the Himalayas, is the official legal border between China and India. But China has never accepted it.

The China-India border dispute covers nearly 3,500 km (2,175 miles) of frontier that the two countries call the Line of Actual Control. The two nuclear-armed neighbours have a chequered history of face-offs and overlapping territorial claims along the poorly-drawn LAC separating the two sides. The LAC is poorly demarcated because the presence of rivers, lakes and snowcaps means the line can shift. Representing two of the world’s largest armies, the soldiers on either side had come face to face at many points. The two countries fought a bitter war in 1962 that spilled into Ladakh. In this war, India was humiliated and it lost a lot of its territory; Beijing retained Aksai Chin, a strategic corridor linking Tibet to China. Both sides see the area as strategically, economically and militarily important. India still claims the entire Aksai Chin region as well as the nearby China-controlled Shaksgam valley in northern Kashmir as its own.

The tension between the two nations spilled over in 2017 in the Doklam area of the Himalayas after Indian troops moved in to prevent the Chinese military from building a road into territory claimed by Bhutan, an ally of India. The Doklam plateau is strategically significant as it gives China access to the so-called “chicken’s neck” or Siliguri Corridor, which is a narrow stretch of land of about 22 kilometres connecting India’s seven north-eastern sister states with the mainland. These seven states, i.e. Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura, have always remained simmering with independence movements like Indian-occupied Kashmir, and have mostly been ruled by local nationalist political parties. Both sides withdrew troops in late August of that year and issued vague remarks about a resolution. Exactly what was decided behind the scenes was unclear, though reports that China had halted construction of the motorway suggested that Beijing backed down.

In 1993, by inking the “Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility,” both India and China agreed to “peaceful and friendly consultations” to resolve the boundary dispute. It was agreed not to use force and to respect the LAC. The agreement stipulated that any “contingencies or other problems arising in the areas” were to be dealt with “through meetings and friendly consultations between border personnel of the two countries.”

Several rounds of talks in the last three decades have failed to resolve the boundary dispute. After the recent bloody clash, the resumption of immediate contact between the Indian and Chinese leadership brought signs of relief to the region. Top Chinese and Indian generals held high-level talks in a Himalayan outpost in a bid to end the latest border standoff, which has seen thousands of troops amassing on both sides of the disputed border, between the world’s two most populous nations. The talks were held in the border outpost of Maldo on the Chinese side of the LAC—de-facto border between the two countries. Similar reconciliation attempts have stalled in the past. The communication may prevent the escalation of the conflict temporarily, but without a permanent solution, the probability of escalation remains.

A strain in the relationship between New Delhi and Beijing was expected to take place not only because of border issues, but also due to broader opposing geopolitical interests. Last month, Narendra Modi-led BJP government put curbs on Chinese investment, an act Beijing called ‘discriminatory’. India’s support for Tibet and its growing security and defence ties with the United States, Japan and Australia have also earned suspicion from Beijing. The conflict between India and China has initiated a new cold war in the region. In the long term, India will be bent upon harming more the Chinese economic interests.

China’s closer ties with Pakistan, which has long-running disputes with India, as well as Nepal have not pleased New Delhi either. Moreover, China’s ‘too big to fail’ Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and its massive defense budget pose a serious geopolitical threat to India. China’s defense budget at $261 billion is more than three times that of India at $71 billion.

As for Pakistan, the Chinese move came as a blessing in disguise as it unquestionably proves the point that Kashmir is an unsettled international dispute as per United Nations resolutions, Ladakh is a part of Kashmir and thus, regionally, it is a tri-lateral issue involving three being nuclear powers, i.e. Pakistan, India and China, and thus this flashpoint has to be addressed on priority basis by the UN Security Council. Understandably, due to its evolving ties with China and rivalry with India, Pakistan has been viewing the Ladakh standoff through a Chinese lens.

The episode has gained substantial space in mainstream Pakistani media. Ever since the deadly standoff between China and India started, Pakistan has been trying to cash in on the situation. From diplomatic manoeuvring behind the scenes to publicly bashing India for the overall developments surrounding Ladakh, Pakistan has stood on the side of China. Even though the extent of China’s moves along the border remain fuzzy, it is clear that Beijing is putting heavy military pressure on India and its territorial claims. For Islamabad, seen from the zero-sum perspective that often frames India-Pakistan relations, this is an unequivocally good thing and the Sino-Indian border clash is a chance to press the advantage on the Kashmir issue. Some analysts conclude that the conflict might lessen tensions along the Line of Control (LoC) between India and Pakistan, and provide breathing space to Kashmiris in Indian-administered Kashmir. The skirmishes between these two don’t match the ones between India and Pakistan where civilian casualties happen more frequently.

Strategic analysts raised the alarm that prevalent tensions between the nuclear-armed neighbours could turn into unintended full-blown military action. When soldiers from the two most populous countries in the world, which spend more than $300 billion on their militaries, have a stand-off, it is a thing of concern to many. If the two countries face a showdown on the border issue, the entire Himalayan region and the Indian Subcontinent will face instability. No external force can change this. Maintaining peace along border areas and friendly cooperation is in line with the two countries’ interests.

Thus, the ongoing tensions must be addressed in a serious manner. In a region where there are three nuclear states, war cannot be an option. Ideally, a dialogue involving Pakistan, India and China can address thorny issues bedevilling their relations and create the necessary grounds for peace and progress in the entire region. If one side doesn’t blink soon, the consequences of this brewing nightmare will be disastrous for the people of this region.

The writer is a Civil Servant from the 47th CTP. He holds an MPhil degree in Sociology and is currently working as a Section Officer (UT).

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.