China International Development Cooperation Agency

Foreign Aid with Chinese Characteristics

China has fast changed its course of economic development at the turn of the century, from being a major recipient of global funds to a net provider of financial assistance. Following the National People’s Congress in March 2018, Beijing set up the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) to oversee its massive, globe-spanning foreign aid and investment activities. This new agency, which answers to the State Council, plans to consolidate the roles and functions that have traditionally been shared by the ministries of commerce and foreign affairs. If it is empowered to do so, the CIDCA could help China coordinate its aid portfolio more efficiently and give Chinese decision-makers a better grasp of the local contexts they are operating in.

During the past four decades, China has transformed itself from a major recipient of foreign aid into a critical provider of investment and development resources for the Global South. However, China’s foreign aid program has been the subject of recurring but gradual reforms—a trend that mirrors the country’s overall economic trajectory and one that continues today. The reform of the Chinese aid system reached a peak in April 2018, when China established a new International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) at the vice-ministry level, elevating the political importance of development cooperation. The new agency is said to be responsible for strategic guidelines and policies on foreign aid; coordinating and making suggestions on major related issues; reforming the foreign aid system; and making plans and overseeing their implementation. Although the CIDCA has been tasked with lofty goals, near-term expectations must be tempered by lingering questions about how it fits into the country’s existing foreign aid bureaucracy. After all, China has been providing foreign aid for decades, and the Chinese international development community has been calling for a bilateral aid agency since the early 2000s. Examining the history of Chinese foreign aid and the logic behind the CIDCA’s founding can help contextualize its status and the role it will play.

Evolution of Chinese Foreign Assistance

Under the current regime in Beijing, China’s practice of sending resources to neighbouring countries goes back to the early 1950s, although some of this assistance does not fit neatly within a modern conception of ODA. Facing the pressure of perceived U.S. containment efforts and U.S. foreign aid programs in Asia, China launched its own self-described external assistance programs, which included military and food assistance to North Korea and Vietnam to support their struggles against U.S. and French military forces, respectively, in the early 1950s.

Under the current regime in Beijing, China’s practice of sending resources to neighbouring countries goes back to the early 1950s, although some of this assistance does not fit neatly within a modern conception of ODA. Facing the pressure of perceived U.S. containment efforts and U.S. foreign aid programs in Asia, China launched its own self-described external assistance programs, which included military and food assistance to North Korea and Vietnam to support their struggles against U.S. and French military forces, respectively, in the early 1950s.

China’s approach to foreign assistance gradually coalesced around a set of principles emphasizing recipient countries’ sovereignty and mutual benefit. In 1964, during a visit to Accra, Ghana, then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai unveiled a formalized set of ideas that Beijing still describes as governing China’s approach to foreign aid known as the Eight Principles. These staples of Chinese diplomacy include precepts like sovereign independence, noninterference in the domestic affairs of other countries, and equal cooperation. Meanwhile, China engaged in bouts of so-called checkbook diplomacy to compete with Taiwan for diplomatic recognition, funding large-scale aid projects in many African countries and elsewhere, such as the TAZARA Railway connecting Tanzania and Zambia.1 These expenditures put a huge burden on the Chinese economy and prompted some foreign critics to accuse China of supporting only socialist leaders. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, large foreign aid projects had become part of chairman Mao Zedong’s legacy: foreign aid amounted to 5.9 percent of total government spending from 1971 to 1975, peaking at 6.9 percent in 1973.2

As its reform period got under way in the late 1970s, China began to restructure its aid programs. After Beijing and Washington established diplomatic relations in 1979, Chinese leaders became less concerned with their competition with Taipei for international support. Hence, China stopped offering new aid projects and devoted itself to maintaining the projects it had already established in the Global South.

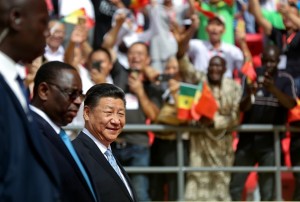

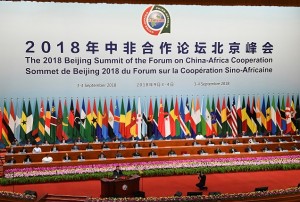

This trend continued until China began reforming the institutions tasked with administering its external aid in the mid-1990s. At that point, the Chinese government established an inter-ministry coordination system on foreign aid that involved an array of state organs, including the Ministry of Commerce, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the Ministry of Education, and the Ministry of Agriculture. More importantly, two new policy banks were launched in 1994, the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank. Beijing started stating that its foreign aid was designed to pursue common development rather than offer recipients one-way benefits. And the two banks gradually became the pillars of China’s foreign aid and development finance. In 2000, Chinese foreign aid began to garner international attention when the country hosted the first Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, a new multilateral venue that soon began to function as the main platform for cooperation between Beijing and its African partners.

More recently in late 2013, under President Xi Jinping, Beijing renewed its commitment to financing major infrastructure projects in other countries by announcing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The initiative quickly became a leading component of China’s overall foreign policy and set off another round of reforms to the country’s foreign aid programs. These latest reforms are meant to achieve multiple goals. First, these changes aim to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of China’s foreign aid by cleaning up the country’s foreign aid system. Second, in response to foreign criticism for mixing commercial deals with development assistance, Beijing intends to differentiate its foreign aid from commercial financing packages. Third, China seems to want to integrate into its foreign aid portfolio and the BRI a greater range of socially conscious development projects, in areas such as agriculture, public health, and education.

The Case for a Chinese Development Agency

China wields great influence in many developing countries through its investments and aid, the latter of which largely consists of grants and concessional loans. For instance, many African countries have received large shares of Chinese aid over the past two decades, a list that includes seven of the top ten recipients of Chinese aid during this period. Elsewhere, countries in Southeast Asia, the former Soviet Union, and Latin America account for a much larger number of so-called infrastructure megaprojects (those with a financial value exceeding $1 billion) than Africa. Hence, the logic behind the new agency is not difficult to understand. As China’s aid and development spending have grown in prominence, many new actors have emerged. The BRI has further complicated China’s aid-related operations, and the old aid coordination system failed to regulate Beijing’s development activities and improve their efficiency. As China has become a major global donor, media outlets around the world have closely scrutinized its behaviour in developing countries. Given that, establishing a single agency to coordinate development aid was a natural move.

First, the CIDCA might distinguish China’s foreign aid from more commercially oriented financial flows. Since the early 2000s, established donors have questioned whether Chinese aid to Africa, for instance, conforms to standard OECD conceptions of development assistance. The Chinese government has issued two official documents—the 2011 and 2014 editions of the “White Paper on China’s Foreign Aid”—stating that most of the financial flows in question were never included in the official foreign aid budget, but these critiques have worsened over time. Some observers have accused Beijing of being a rogue donor and practicing neocolonialism and debt trap diplomacy. Beyond the problem of transparency, another reason for these critiques is that these financial flows were controlled and monitored by the Ministry of Commerce, which is meant to promote trade and investment, not oversee development in other countries. The newly established CIDCA will be in charge of the financial flows that are concessional in nature (or the parts that qualify as ODA), such as grants as well as no-interest and concessional loans. Meanwhile, the commercial financial arrangements, such as preferential buyers’ credits and equity investments for development purposes (from investment funds such as the China-Africa Development Fund under the China Development Bank, or the China-Africa Industrial Cooperation Fund under the Export-Import Bank of China), will remain under the control of the Ministry of Commerce. China hopes the reputation of its foreign aid programs will improve if the country better distinguishes between different financing vehicles and provides a clearer picture of its development assistance practices.

Second, the CIDCA will strive to become a unified actor at the center of China’s foreign aid system. Previously, Beijing relied on a coordination system among several ministries and policy banks instead of a single agency to oversee its aid portfolio. Not surprisingly, the interests and goals of those actors were not always aligned, which undercut the efficiency and effectiveness of China’s overseas development efforts. This coordinating function will be particularly important to the CIDCA because China’s aid budget grew at an annual rate of about 14 percent between 2003 and 2015. Understandably, all the ministries involved in this policy process wanted a larger share of these funds. A unified agency tasked specifically with foreign aid will aim to ease the tensions among these competing ministries and improve the performance of China’s aid programs.

Helping to facilitate BRI projects is another function of the newly established CIDCA. The BRI poses great challenges to China’s foreign aid programs since new agencies and bilateral and multilateral development finance institutions have been created to support it. The old policy coordination system could not operate effectively with the many new players, such as the New Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Silk Road Fund, and other more narrowly focused entities. With the CIDCA now in place, in theory, there will be only one agency managing all the aid-related projects among all the aforementioned institutions.

Third, the CIDCA will aim to promote studies and policy recommendations pertaining to Chinese foreign aid. Compared to many Western countries, China has not invested enough in researching international development, a subject studied in only a few universities and institutes. The government officials working on aid can barely keep pace with the growth of China’s aid-related expenditures. Most traditional donor countries are equipped with a fairly strong capacity for research on a wide range of subjects regarding aid, usually via their bilateral aid agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development. By contrast, the Chinese government possesses a somewhat limited research capacity for aid-related activities, especially in terms of on-the-ground project implementation. It is not feasible for only a few individuals from the economic and commercial counselor’s office (in-country Ministry of Commerce representatives) to work on all of China’s development projects. A unified agency with strong foreign aid research capabilities would help improve efficiency by helping the central government choose which projects to support.

Third, the CIDCA will aim to promote studies and policy recommendations pertaining to Chinese foreign aid. Compared to many Western countries, China has not invested enough in researching international development, a subject studied in only a few universities and institutes. The government officials working on aid can barely keep pace with the growth of China’s aid-related expenditures. Most traditional donor countries are equipped with a fairly strong capacity for research on a wide range of subjects regarding aid, usually via their bilateral aid agencies such as the United States Agency for International Development, the Japan International Cooperation Agency, and the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development. By contrast, the Chinese government possesses a somewhat limited research capacity for aid-related activities, especially in terms of on-the-ground project implementation. It is not feasible for only a few individuals from the economic and commercial counselor’s office (in-country Ministry of Commerce representatives) to work on all of China’s development projects. A unified agency with strong foreign aid research capabilities would help improve efficiency by helping the central government choose which projects to support.

Bureaucratic Setup

The bureaucratic setup of the new CIDCA seems to be a continuity of the country’s commercial focus towards foreign aid. The bureaucratic ranking of CIDCA is set at the vice-ministerial level. The director, Wang Xiaotao, was the former deputy director of the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s top economic policymaking organ. The first two deputy directors of CIDCA came from MOFCOM and the MFA, respectively, reflecting the two pillars China’s foreign aid has been and continues to be anchored on. In particular, Deputy Director Zhou Liujun used to be in charge of service trade and foreign direct investment at MOFCOM. In comparison, the deputy director from the MFA, Deng Boqing, was Chinese ambassador to Nigeria. In early 2019, a third deputy director—former deputy director of the National Intellectual Property Administration, Zhang Maoyu—was added to CIDCA’s leadership, which suggests an emphasis on intellectual property issues within the framework of China’s foreign aid.

Mandate

CIDCA’s mission statement suggests subtle yet important distinctions in its mandate and authority in comparison with its previous incarnation as the Department of Foreign Aid at MOFCOM. Instead of the implementation of specific projects, CIDCA is geared more toward the strategic design, management, and interagency coordination of China’s foreign aid administration. For example, the 2018 Draft Foreign Aid Management Methods identified new tasks for CIDCA including strategic planning, monitoring and evaluation, aid reform, and budget preparation.

Another key distinction lies in the concrete project implementation side: Although CIDCA is responsible for the planning and coordination of foreign aid, it is not responsible for their implementation. The implementation will remain the responsibility of the individual relevant functional agencies, such as the Ministry of Commerce and the Ministry of Agriculture. Furthermore, CIDCA is responsible for developing country strategies and signing aid projects as the face of China’s foreign aid. In the “Cooperation Activities” section of CIDCA’s website, seven bilateral cooperation agreements were listed between June and December of 2018 where CIDCA signed economic development agreements on behalf of China. CIDCA has already had active engagement with multilateral institutions such as the United Nations and World Bank, as well as traditional donors such as the U.K., EU, Australia, and Norway.

Setting Realistic Expectations

The CIDCA falls directly under the State Council, the country’s highest administrative body, and combines the foreign aid branches of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Commerce. Although the agency’s founding is an encouraging development, it is important to temper expectations, especially since the CIDCA’s status as a deputy ministry might limit its implementation capacity. There are several hurdles on the horizon. First, it might be difficult to expand the size of the CIDCA’s staff. Without sufficient resources, the agency may struggle to wholly fulfill its governance and research functions. Second, it could be challenging for a deputy ministerial–level agency to coordinate foreign aid projects under other ministries, such as the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health, and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Third, China’s development agency might encounter difficulties trying to monitor and supervise some state-owned enterprises led by the central government, since they are of the same rank as deputy ministries in the country’s administrative and bureaucratic chain of command.

So, while the logic behind the CIDCA is fairly clear, the actual role of the new agency in China’s foreign aid system will continue to be fine-tuned. The launch of the CIDCA is a reassuring initial step for China’s efforts to reform its foreign aid, but more measures and steps will be needed over time for the new agency to fulfil its intended functions.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.