India South Asia’s hegemon

At India’s bidding, smaller countries in South Asia toe the Indian line in regard to the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation and other international forums. In 2005, Washington showed its intention ‘to help India become a major world power in the 21st century (K. Alan Kronsstadt, Congressional Research Service Report for Congress, India-US Relations updated, February 13, 2007, p.4). It was later re-affirmed by US ambassador David Mulford in a US embassy press release dated March 31, 2005. This resolve later translated into modification of domestic laws in order to facilitate export of sensitive military technology to India. The Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) also relaxed its controls to begin exports to India for its civilian nuclear reactor (enabling the country to divert resources to military use).

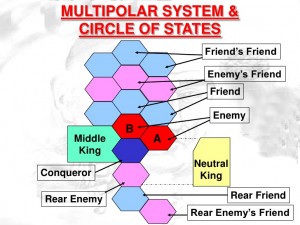

Raja Mohan, Shyam Saran and several others point out that India follows Kautliya’s mandala (concentric, asymptotic and intersecting circles, inter-relationships) doctrine in foreign policy. It is akin to Henry Kissinger’s ‘spheres of influence’. According to this doctrine, all neighbouring countries are actual or potential enemies. However, short-term policy should be based on common volatile, dynamic and mercurial interests, like intersecting portion of two circles in Mathematical Set Theory.

India’s current policy

India’s former foreign secretary, Shyam Saran, in his book ‘How India Sees the World’ says, “Kautliyan [Chanakyan] template would say the options for India are sandhi conciliation; asana neutrality; and yana, victory through war. One could add dana, buying allegiance through gifts; and bheda, sowing discord. The option of yana, of course, would be the last in today’s world’ (p. 64, How India Sees the World: Kautilya to the 21st Century). It appears that Kautliya’s and Saran’s last-advised option is India’s first option, with regard to China and Pakistan, nowadays.

Raja Mohan elucidates India’s ambition, in terms of Kauliya’s mandala, to emerge as South Asian hegemon in following words:

“India’s grand strategy divides the world into three concentric circles. In the first, which encompasses the immediate neighbourhood, India has sought primacy and a veto over actions of outside powers. In the second, which encompasses the so-called extended neighourhood stretching across Asia and Indian Ocean littoral, India has sought to balance other powers and prevent them from undercutting its interests. In the third, which includes the entire global stage, India has tried to take its place as one of the great powers, a key player in international peace and security. (C. Raja Mohan, India and the Balance of Power, Foreign Affairs, July-August 2006).

Henry Kissinger views Indian ambitions in the following words:

“Just as the early American leaders developed in the Monroe Doctrine concept for America’s special role in the Western Hemisphere, so India has established in practice a special positioning in the Indian Ocean region between East Indies and the Horn of Africa. Like Britain with respect to Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, India strives to prevent the emergence of a dominant power in this vast portion of the globe. Just as early American leaders did not seek approval of the countries of the Western Hemisphere with respect to the Monroe Doctrine, so India in the region of its special strategic interests conducts its policy on the basis of its own definition of a South Asian order.” (Henry Kissinger, World Order (New York, NY: Penguin Press, 2014, p. 205).

Zbigniew Brzeszinsky takes note of India’s ambition to rival China in the following words:

“Indian strategies speak openly of greater India exercising a dominant position in an area ranging from Iran to Thailand. India also positions itself to control the Indian Ocean militarily, its naval and air power programs point clearly in that direction as do politically-guided efforts to establish for India strong positions, with geostrategic implications in adjoining Bangladesh and Burma [Myanmar].” (Brzeszinsky, Strategic Vision: America and the Crisis of Global Power).

Robert Kaplan, in his book, ‘Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and Future of American Power’, argues that the geopolitics of the twenty-first century will hinge on the Indian Ocean. USA’s new protégé is India. To woo India firmly into its fold, USA offered to sell India US$ 3 billion (per one unit) Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) and Patriot Advance Capability (PAC-3) missile defence systems as an alternative to Russian S-400 system. India ditched Russia from whom it had decided to purchase five S-400s air defence systems at the cost of US$5.4 billion.

With tacit US support, India is getting tougher with China. There was a 73-day standoff on the Doklam (Donglang in Chinese) plateau near the Nathula Pass on Sikkim border in 2017. Being at a disadvantage vis-à-vis India, China was compelled to resolve the stand-off through negotiations. In later period, China developed high-altitude “electromagnetic catapult” rockets for its artillery units to liquidate Indian advantage there, as also in Tibet Autonomous Region. China intends to mount a magnetically-propelled high-velocity rail-gun on its 10,000-ton-class missile destroyer 055 being built.

India’s ambition to emerge as South Asia’s hegemon is reflected in its successive defence budgets. Aside from showcased marginal increase in defence budget, the three services have been asked to devise a five-year model plan for capital acquisitions. The Indian navy wants a 200-ship strong fleet by 2027. Navy Chief Admiral Karambir Singh had, in December 2019, pointed out that China added over 80 ships in the last five years. Navy wants to procure six new conventional submarines under Project 75-I and 111 Naval Utility Helicopters to replace the vintage fleet of Chetak choppers. Indian air force wants to procure 114 new fighters for the IAF besides the 36 Rafales ordered in 2015, still in the process.

To hoodwink general reader, India deflates its defence expenditure through clever stratagems. It publishes its ‘demands for grants for defence services’ separately from demands for grants of civil ministries that include MoD. She clubs military pensions in civil estimates. There are several other quasi-defence provisions that are similarly shoved in civil estimates. Such concealed defence provisions include public-sector undertakings under MoD like dockyards, machine tool industries (Mishra Dhatu Nigham), and Bharat Heavy Electrical Limited, besides space-and-nuke-research projects, border and strategic roads and a host of paramilitary forces (Border Security Force, Industrial Reserve Force, etc).

Why India does so? It does so to ‘lower’ its defence budget as proportion to Gross National Product. The real problem is that a hike in India’s defence outlays, at the cost of social sectors, ratchets up Pakistan’s defence expenditure. Spending spree for conventional weapons between nuclear peers is not understood? Each year, increase in India’s defence outlay ratchets up Pakistan’s defence outlay.

Let India lower her expenditure first! Be a leader to compel Pakistan to follow suit.

Shun hegemonic designs, at least for the time being.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.