Water Disputes with

India and Afghanistan

Water is a basic human right but the population explosion, technological boom and high demand for water has led to a global water shortage that is endangering millions around the world. Pakistan, especially, is in trouble as both its eastern and western neighbours, being hostile to the country, are putting in collaborative efforts to create an acute water crisis for it. On the eastern side, Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi, has persistently threatened to block the flow of water from India into Pakistan despite the fact that both countries have signed the Indus Waters Treaty of 1960. On the western side, Afghanistan is pushing, in collaboration with India, to build dams to store and regulate water, which is an indirect blow to Pakistan. This is a critical situation that demands prudence and all-out efforts on the part of Pakistan authorities. Hence, there is a pressing need to open diplomatic channels for ‘hydro diplomacy’ so as to address water management issues among India, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Roughly two-thirds of the 263 transboundary lake and river basins that cover almost half the Earth’s surface, and are home to about 40 percent of the world’s population, do not have a cooperative management framework. As many as 145 States have territory in these basins, and 30 countries lie entirely within them. There are approximately 300 transboundary aquifers, helping to serve the 2 billion people who depend on groundwater. Cooperation is, therefore, essential, especially in areas vulnerable to the impacts of climate change and where water is already scarce. Population growth, socio-economic development, and mismanagement of existing water supplies across the world, are expected to combine with climate change threats to challenge the ability of many countries, some already resource-stressed, to meet their domestic water needs. This can threaten human security, food security, national security, and regional stability. Across the world, increasing threats to the available supply of water can disrupt food security as the greatest consumer of water is the agricultural sector.

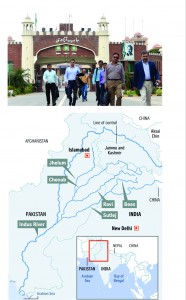

In the face of these threats, Pakistan and its neighbours need to strengthen water management on the two transboundary river basins—Indus and Kabul. Both the river basins are critical for the food, energy and human security needs of the countries’ populations. While the Indus River shared with India is governed under the Indus Waters Treaty, 1960, the Kabul River has no cooperative arrangement between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Even the treaty with India on water-sharing overlooks the many vulnerabilities of the Indus Basin—including climate change, environmental flow management and socio-economic development. The Indus is the world’s most vulnerable water tower owing to high dependence downstream and greater impact of climate change, socio-economic development and associated rises in water use, and geopolitical instability. Management of transboundary water upstream and downstream also holds true for provincial boundaries within Pakistan.

Scenario with Afghanistan

When it comes to Afghanistan, we find that the country is currently experiencing a 60 percent drop in the rain and snowfall needed for food production. The rapid expansion of Kabul’s population, extreme drought conditions across the country and the specter of climate change is also said to have exacerbated the need for new water infrastructure. A 2017 study by Afghan, German, and Finnish universities stresses that Afghanistan desperately needs better water infrastructure and water management. Afghanistan is in the process to construct the Shahtoot Dam on Maidan River, an upper tributary of Kabul River in the Chahar Asiali district of Kabul Province. This dam will hold 146 million cubic meters of potable water for two million Kabul residents and irrigate 4,000 hectares of land. It will also provide drinking water for a new city on the outskirts of Kabul called Deh Sabz. But building dams on the Kabul River is said to be a politically complicated matter; the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region is said to be defined by its complex maze of trans-boundary rivers and there is no legal framework in place to avoid major conflict between the nations.  And the development is said to be fueling fears downstream in Pakistan that the Shahtoot Dam which is being funded and built by India will alter the flow of the Kabul River and reduce the water flows into Pakistan that could severely limit the country’s future access to water. The Pakistani media has already reported that there could be a 16 to 17 percent drop in water flow after the completion of the Shahtoot Dam and other planned dams. According to the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations’ 2011 report on water security in Central Asia, “Providing the right support by India (while constructing the Shahtoot dam) can have a tremendous stabilizing influence, but providing the wrong support can spell disaster by agitating neighbouring countries.”

And the development is said to be fueling fears downstream in Pakistan that the Shahtoot Dam which is being funded and built by India will alter the flow of the Kabul River and reduce the water flows into Pakistan that could severely limit the country’s future access to water. The Pakistani media has already reported that there could be a 16 to 17 percent drop in water flow after the completion of the Shahtoot Dam and other planned dams. According to the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations’ 2011 report on water security in Central Asia, “Providing the right support by India (while constructing the Shahtoot dam) can have a tremendous stabilizing influence, but providing the wrong support can spell disaster by agitating neighbouring countries.”

Shahtoot Dam and Indo-Afghan Nexus

Beyond reducing water flow to Pakistan, the Shahtoot Dam has a unique capacity to escalate tensions in the region, thanks to its funding from India. India has made major investments in Afghanistan’s infrastructure in recent years—from highway construction to repair of government buildings and dams damaged by conflict.

Since 2001, India has pledged about $2 billion total in development projects in Afghanistan. And while Afghan analysts have made the case that the dam is critical to surviving future water shortages in Afghanistan, Pakistani officials in Islamabad are casting India’s investment in a harsher light, contending that the dam is merely the latest move in India’s grand plan to strangle Pakistan’s limited water supply. Because Pakistan has failed to build enough hydropower infrastructure at home, some Pakistanis fear it might have to buy electricity from Afghanistan in the future.

State of affairs in India

Last year, many Indian states faced severe water scarcity. The situation deteriorated further as we witnessed the second driest pre-monsoon season in the last 65 years. According to the Drought Early Warning System (DEWS), the problem is worrying as the drought-like situation covers more than 44 percent geographic area, an increase of 11 percentage points over a year ago. In a recent report, India’s leading business daily, ‘The Hindu BusinessLine’, quoted India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences and the Ministry of Science and Technology as saying they have “found a significant increasing trend in the intensity and areal coverage of moderate droughts over India in recent decades”. It added that “more intense droughts have been observed over North and Northwest India and neighbouring Central India”.

Since 2015, drought has become more widespread in India – with the exception of 2017. The spell of drought last year emptied hundreds of villages across different states as people fled extremely high temperatures abandoning homes in search of water and solace from the scorching sun. The acute water shortages have destroyed agriculture-based livelihoods as crops like cotton, maize, soya, pulses, and groundnuts have withered devastating local economies. In the past, crop failures and mounting debts have pushed hundreds of thousands of farmers to commit suicide, a trend that has seen a phenomenal increase in the last decade.

The politics of India and Pakistan adds yet another, and potent, twist to the growing water crisis in the region. The increasing mutual trust deficit and growing rhetoric of the Indian leadership are fuelling speculations about a future ‘water war’ with Pakistan.

Case of Pakistan

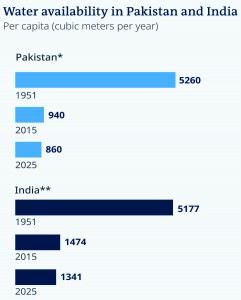

In Pakistan, the situation is no different. Drought has become a frequent phenomenon with the drought of 1998-2002 considered the worst in the country’s history. The express lack of any serious official planning coupled with corruption, uncontrolled human population, urbanisation, and absence of water management has aggravated the issue. A 2017 report from the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) claimed the country had touched the “water stress line” in 1990, and a decade and a half later, it crossed the “water scarcity line” in 2005. The country is supposed to reach the “absolute scarcity” level of water by 2025.

Growing seasonal afflictions such as delay in the monsoon season or failure to get enough rains exacerbate the situation as rainfall has been steadily declining; this, according to experts, is being mainly linked to climate change. In Sindh and Balochistan, drought has almost become a permanent feature with deaths being reported regularly from Sindh, particularly in Tharparkar. But amid increasing political rancour and the perennial tussle between various state institutions, there is hardly any time to think about the future that, by various scientific studies, is not too distant in future and carries extremely grim predictions. Any failure in agriculture would choke Pakistan’s lifeline as about 60 percent of its GDP depends on agronomy.

The availability of water means everything to Pakistan, an agricultural nation with the world’s most interconnected irrigation system. This was why the government began the Diamer-Bhasha dam project, which would, to some extent though, neutralise external water threats by ensuring adequate water storage in the country. But, it must also be kept in mind that despite having signed a treaty with Pakistan, India has intermittently threatened to block Pakistan’s share of water flowing from its borders. Besides Modi’s tantrums, in February last year, Nitin Gadkari, India’s then water resources minister, publicly alluded to the “calls for India to prevent even a single drop of water from going to Pakistan”. While such pronouncements may be dismissed as hot air, they are bound to heighten existential anxieties and support permanent escalation further constricting any room for engagement. Some alarmist suggestions foresee an immediate nuclear war should India realise the threat. So we need to be aware of and prepare for in case of any conflict.

Conflict resolution with:

- Afghanistan

A water-sharing treaty between Pakistan and Afghanistan could, it is believed, potentially help promote the irrigation techniques used and determine the types of hydroelectric projects that can be built along the Kabul River basin. Afghanistan and Pakistan must, therefore, urgently start paying attention to regional hydro-diplomacy. The first step is to support the gathering of data, which would be shared with all neighbours, and potential scientific forecasts of the planned dams’ impacts on water flow. Scientists need to be involved with international diplomatic and scientific support.

- India

Unless Pakistan and India commit to solving the bilateral water issues through effective hydro-diplomacy in line with the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), a war between the two countries may break out in future.

Conclusion

With rising water demand and declining availability, along with the pressures of increasing climatic variation and climate change, Pakistan needs to work with both India and Afghanistan towards collaboration in the governance systems of water management, beginning with joint monitoring and assessment of shared waters with both its neighbours. Such collaborations will eventually help move towards implementation of some form of an integrated river basin management framework for optimising and sustaining the use of available water resources. South Asian countries could use their shared water resources for attacking poverty and achieving economic development by implementing a mechanism to monitor and assess shared water, and by collaborating closely with one another to resolve their water-sharing disputes.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.