The Coming Refugee Crisis Syria VS Russia the EU..

Europe’s most serious humanitarian crisis of the 21st century, long in the making but recently in hiding, has resumed with scenes of chaos and despair at the Greek border. Turkey’s opening of its borders with two EU members, Bulgaria and Greece, in the wake of a Syrian strike that killed 34 Turkish soldiers on 27 February, a tragedy began to unfold: Turkey decided to open its border for refugees to cross into Europe, effectively halting the 2016 migration deal it stuck with the European Union. Thousands of refugees, camped out in the open, are clinging to a sliver living of hope that they will be able to cross into Europe.

Background

For a war that has supposedly been won, Syria continues to bleed refugees at an alarming rate. Idlib, a city in the country’s northwest, is the final rebel holdout that keeps Bashar al-Assad—and his Russian backers—from complete victory in his country’s nine-year civil war. While the West has largely disengaged from the Syrian conflict, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has continued his offensive in the country, both to prevent Kurds in neighbouring Syria from successfully establishing a territory for themselves, and as a way of ensuring that his country doesn’t get flooded by yet another wave of refugees.

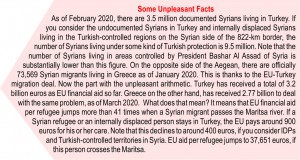

It is no coincidence that the abrupt decision to open the border has come at a time of massive mobilisation of Turkish troops inside Idlib. Turkey aims to prevent a wholescale onslaught by Russia and the Syrian regime there, which would drive some of its 2.7 million inhabitants towards the Turkish border. The majority of Syrians who live in Idlib have family members who joined the ranks of the opposition or fled from other parts of Syria to escape the Assad regime. As they will not go back to regime-held Syria, and with the Turkish-Syrian border firmly sealed, they are trapped. Already hosting 3.7 million Syrians, Turkey does not want to be in a position to have to accept more.

The issue of forced migration and internally displaced persons (IDPs) is perhaps the most defining problem of our age, and the civil war in Syria is its most typical case. It is very difficult to deal with because it’s a regional problem that can only be addressed through global cooperation. In earlier March, Turkey announced its decision to not host the refugees anymore saying it had ‘reached its capacity’ and opened its borders to allow the refugees’ passage to Europe. Thousands have since massed at the Greek border, triggering fears of an influx like that which poisoned European politics in 2015. These refugees are once again being seen as pawns in a geopolitical game, as chinks appear in “Fortress Europe”.

Why Erdogan opened borders?

Erdogan’s first motivation is to gain European support, politically and financially, in his quest to establish a safe zone inside Idlib, in preparation for a potential influx of internally displaced persons.

Domestic considerations are also a factor in Ankara’s decision to push migrants towards the border. With news of Turkish casualties from the Idlib front and the government’s Syria policy under growing public scrutiny, Erdogan must also hope that polemic on migration will shift the domestic debate away from Syria and towards Euro-bashing. An attack that killed 36 Turkish troops has fuelled a bitter internal debate on Turkish engagement with Syria. To Erdogan’s critics, the crisis in Idlib is a consequence of his failed Syria policy, and not a “fight against terrorism,” as they believed previous incursions to be.

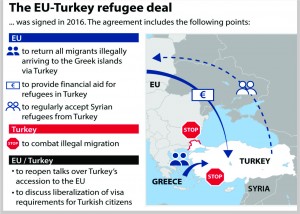

Then, of course, there is Turkey’s desire to renegotiate the 2016 refugee agreement with the EU for a new tranche of financial aid. Facing real budgetary difficulties and jittery markets, Ankara hopes that a new financial agreement with the EU will promote a positive image of the economy and reverse the decline in support for Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party.

Erdogan has long complained that the EU has not lived up to its end of the bargain, even though the bloc has already paid Turkey around half of the €6 billion specified under the deal and the rest is, according to EU officials, already “contracted out” to be paid by 2022. Here, domestic political considerations have merged with financial ones. Turkey’s refugee policy is unpopular and, at a time of economic downturn, many Turks see Syrians as the cause of their predicament, taking up a refugees-out narrative. This is also the reason why the government is wildly exaggerating the number of refugees who have left Turkey—to as much as 140,000—while EU officials discuss crossings of the Aegean as being “in the thousands”.

Europe’s regulatory framework, which only allows for payments to specific institutions and projects (as opposed to a direct payment to the Turkish government) has long frustrated Ankara. And Erdogan hopes that his government can gain more autonomy over the funds this time.

How Will EU deal with the crisis?

The chaos triggered by more clashes and deaths at the Greek border risks hardline measures from Europe as the bloc still has nightmares about the mismanaged chaos of the 2015 influx of migrants and refugees, which produced horrible pictures of dead children, masses of unregistered people wandering the roads, political divisions and a significant boost to far-right populism across the continent. Turkey’s vow to let hundreds of thousands more leave for Europe has done more than revive those fears. It has exposed Europe’s failure to use the time bought since 2016, when it made a deal to pay Turkey to house migrants and refugees, to create a coherent migration or asylum policy.

So, Europe once again finds itself in a quandary, trying to tread a line between two NATO members, Turkey and Greece, one trying to push refugees forward, the other striving to keep them out.

There is little doubt that Europe, beyond Greece, wants neither the migrants nor another crisis. Greece, having suspended EU asylum law, is implementing summary deportations and ignoring asylum applications. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen praised Greece as “Europe’s shield,” Brussels has also earmarked €700 million to help Greece deal with the situation.

For the European Union, however, it is an awkward moral clash with its professed values of protecting human rights, individual dignity and the right to seek asylum under international law, which Greece says it has suspended for now.

European Union officials are quietly talking to Turkey about providing further help, but there is no sign that European nations will provide the military support to Erdogan who wants to create a “safe zone” in Idlib as well as a no-fly zone there.

The bloc’s foreign policy chief, Josep Borrell Fontelles, announced 60 million euros worth of aid for the most vulnerable people in northwest Syria after talks in Ankara with Mr Erdogan. Senior EU officials had announced a much larger sum, 700 million euros, in new aid to Athens to help it tackle the migrant crisis.

European officials point out that the border between Idlib and Turkey is tightly shut and that so far there is no new influx of Syrian refugees.

Has Erdogan burned his bridges?

The Turkish president may well have gone too far, prompting EU leaders to lose any appetite for renegotiating a deal with Turkey. Whether Europe will be drawn further into the war in Syria remains to be seen. Likewise, whether this will spark another full-blown crisis, and to what extent this will propel Europe’s political right, is not certain. Whatever the outcome, however, the humanitarian consequences deserve our attention.

Europe has failed to find a humane response to the so-called refugee crisis. The Minniti deals that Italy struck with Libya in 2017 may have reduced the flow of migrants across the Mediterranean by approximately 85 percent, but there were serious human rights concerns. Now, thousands of desperate people are having their hopes raised, only to be dashed as they come up against violence on the ramparts of “Fortress Europe”.

Ceasefire in Syria

In this chaotic state of affairs, Turkish President Erdogan met with Russian President Vladimir Putin to nail down a ceasefire in Idlib. After six hours of intense negotiations on March 5 in Moscow, the parties signed a joint declaration to envisage establishing an immediate cease-fire in the Idlib de-escalation zone, a security buffer zone to the north and south from the M4 highway and the start of Turkey-Russia joint patrols to commence on March 15. Likewise, both countries’ leaders have reaffirmed their belief in the necessity to preserve the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of Syria while considering its division into zones of influence unacceptable.

Erdogan can’t really afford to host any more refugees, either financially or politically. This ceasefire buys him some time and eases the immediate threat of another million people crossing the border into Turkey, but it does not provide a permanent solution to the Idlib mayhem.

The deal buys Europe time as well, as Erdogan will refrain from pushing more refugees up against Europe’s borders. Ceasefire deal or no, Erdogan wants three things from Europe. First, he wants Brussels to lean on Russia to stop its support of Assad troops in Idlib. Second, he wants the EU to start playing a more active role in helping internally displaced people in Syria (primarily to keep them from coming into Turkey). Third, he wants more money from the EU to deal with Syrian refugees in both Syria and Turkey.

But Europe has no interest mixing it up with Putin over Syria, where it’s become clear Russia’s president is far more committed to driving the final outcome there than the Europeans are. European member states are also maximally divided on whether to impose more sanctions on Russia (many of whom rely significantly on trade with Russia), making increased sanctions on Russia over its actions in Syria a non-starter.

However, Europe does want to avoid a repeat of its last immigration crisis, so it’s likely Brussels will hand more funds over to Turkey to manage refugee flows… if Turkey agrees to uphold the migration deal (and if they can agree amongst themselves the funding sources during already-tense budget negotiations). Brussels is also willing to work with Turkey on dealing with Idlib refugees, but is less inclined to help the refugees Turkey has caused by launching offensives against the Kurds in Syria.

Conclusion

The events of the past few days are likely to provide a brief reprieve for both Turkey and Europe from more refugees, but one that is unlikely to last. And this respite comes at the cost of officially giving Putin the power to determine what happens in Idlib, and hence Syria. Keep an eye out for warming weather, too—as the weather improves to make crossings by sea easier and human smugglers are able to restock the supplies they need to resume operations, migration problems are likely to rear their head again.

As a new phase in the war has already begun, a ceasefire in Idlib should serve as a cue for this shift. Starting with Idlib, European leaders must start thinking creatively about stabilisation and reconstruction in war-torn Syria—and, yes, they must do so before the war is even over.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.