Babri Masjid Case and the

International Law

Kamran Adil

Introduction

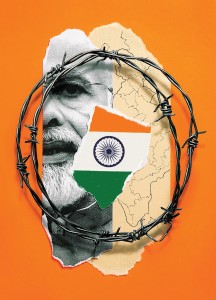

The direction of global events is more towards power and interest-based decision making than towards rule-based system that was installed in the post-Second World War era. The direction is expressing itself in many manifestations. In the context of Pakistan-India relationship, after India’s executive toyed with the legal order of the Kashmir dispute by issuing ultra-vires orders under Article 370 of the Indian Constitution, its judiciary also proved how it was driven in the same direction, where instead of rule of law, rule of necessity under the veneer of procedural law of limitation and without deciding on the merits of the case would reign supreme. On 9th November 2019, the Supreme Court of India passed a copious judgement whereby it decided the long-pending Babri Masjid Case. Quintessentially, the judgement was against the stance of Muslims, and it favoured the mob. The instant write-up will present brief facts of the case and the reasoning employed by the Court, which will be followed by discussion on international law regarding the rights of minorities and cultural properties.

Résumé of the Case

- The Judgement

The case related to Babri Masjid is titled ‘M. Siddiq vs. Mahnat Suresh Das and others’ (M. Siddiq Case). The case was instituted in the Supreme Court of India in 2010 as a Civil Appeal bearing number 10866/2010. The case was heard by a five-member bench of the Court and was headed by the then-Chief Justice of India, Justice Ranjan Gagoi. The judgement is a tome comprising over one thousand pages.

- The Timeline

The timeline of the case is ancient. The Court noted:

“This Court is tasked with the resolution of a dispute whose origins are as old as the idea of India itself. The events associated with the dispute have spanned the Mughal empire (sic), colonial rule and the present constitutional regime.”

Without giving factual details, the Court started its judgement with discussion of five civil suits. However, for factual clarity, it may be stated that though the dispute was old, it came to international limelight when on 6th December 1992, a Hindu rally turned into a mob and demolished the centuries-old Babri Mosque, a religious and cultural site of Muslims in Ayodhya; thereafter, the dispute was styled as ‘Babri Mosque Dispute’ between Muslims and Hindus.

Babri Mosque was built in Ayodhya, probably in 1528, by the order of Babur, a Mughal Muslim Emperor. From that time to 1850s, there was no reported dispute on the issue that became under adjudication at any formal forum. Later, in colonial times, in 1856-57, the site became a point of dispute between Muslims and Hindus. At that time, the colonial government erected a buffer wall dividing the site into inner and outer courtyards leaving the former to the use of Muslims and the latter to the use of Hindus. In 1885, first civil suit was instituted by a Hindu, seeking permission to build temple at the outer courtyard. The suit was dismissed by the civil judge. Two unsuccessful appeals were made against the orders by the Hindus. Then again, in 1934, another conflagration took place between Hindus and Muslims in which the mosque was partially damaged; the colonial government got it repaired at its own expense. Finally, on 22 December 1949, Babri Mosque was desecrated by Hindus, and thereafter, the Muslims were not allowed to carry out prayers there. Under the preventive criminal law, proceedings under Section 145 Criminal Procedure Code were initiated at the site and it remained attached by the magistrate court and was managed by a receiver. These essential facts were then followed by five civil suits that find mention in the judgement of the Supreme Court of India and that were appealed to Allahbad High Court which passed its judgement in 2010 ordering division of the site into three parts: one part going to Muslims, and two parts going to two different groups of Hindus. The judgement of the Allahbad High Court was appealed against in the Supreme Court of India, which announced its verdict on 9th November 2019. As many as 18 review petitions were filed against this judgement, which were also dismissed on 12th December 2019.

iii. Decision

The gist of the decision of the Supreme Court may be summarized into the following points:

- The Indian Government shall set up a trust that will be handed over the possession of the land where Babri Masjid is situated, and shall be handed over possession of its inner and outer courtyards;

- The Indian Government shall also hand over ‘a suitable plot of land measuring 5 acres to Muslims’ Sunni Central Waqf Board for construction of a mosque.

- Reasoning

The nub of the reasoning of the decision can be found in the civil claims made in five civil suits from 1950 to 1989. It means that for legal reasoning, the matter was examined within the legal framework of the postcolonial period and after the independence of India. Out of the five civil suits, four were filed by Hindus, whereas one was filed by Muslims through Sunni Central Waqf Board. The civil suits filed by the Hindus related to title/ownership on the ground that, prior to the construction of the Mosque, there was a temple at the same place, which was constructed there as it was the birthplace of Lord Rama. On the contrary, the claim of the Muslims was that the title belonged to them as it was a Waqf land (trust land) and remained in possession of Muslims since 1528. In the alternate, the Muslims had pleaded that their title was perfected by adverse possession. Both bases of claims of Muslims’ case were rejected by the Court, which treated the matter as more of fact than of law and, therefore, sought evidence on factual part and then interpreted that it did not meet the requirements. For example, it was noted in the judgement that the concept of possession is ‘polymorphous’. The judgement stated:

“It is impossible to work out a completely logical and precise definition of “possession” uniformly applicable to all situations in the contexts of all statutes. Dias and Hughes in their book on Jurisprudence say that if a topic ever suffered from too much theorising it is that of “possession”. Much of this difficulty and confusion is (as pointed out in Salmond’s Jurisprudence, 12th Edn., 1966) caused by the fact that possession is not purely a legal concept. “Possession” implies a right and a fact; the right to enjoy annexed to the right of property and the fact of the real intention. It involves power of control and intent to control.”

Examining evidence at the Supreme Court level is a perilous business and, therefore, the tendency worldwide is to refer legal – and not factual – disputes to the apex courts. Anyhow, the interpretation of factual points by the Supreme Court of India went into determining rights of Muslims, and as a consequence, their claims were dismissed. The claims of Hindus were also dismissed on similar grounds. The basis of the judgement by the Supreme Court was the fact that the land, where Babri Mosque was situated, was state land; this finding is based on the land revenue record that showed the land as ‘Nazul land’ (land owned by government).

International Law

The international law came under discussion as a passing reference in the judgement. The Supreme Court of India was called upon to decide the title/ownership of the land on the basis of ancient and first right. The Court, on the ground of international law, noted that the dispute related to four distinct legal regimes. In paragraph 635, it stated:

“The facts pertaining to the present case fall within four distinct legal regimes: (i) The kingdoms prior to 1525 during which the “ancient underlying structure” dating back to the twelfth century is stated to have been constructed; (ii) The Mughal rule between 1525 and 1856 during which the mosque was constructed at the disputed site; (iii) The period between 1856 and 1947 during which the disputed property came under colonial rule; and (iv) The period after 1947 until the present day in independent India.”

The four legal regimes were treated as acts of sovereigns and the Court found that it could not adjudicate on a right which it cannot enforce:

“… The Privy Council clarified that irrespective of what international law had to say on whether the new sovereign was subrogated into the shoes of the old sovereign with respect to the legal obligations of the latter, a municipal court cannot enforce such legal obligations in the absence of express recognition of the legal obligations by the new sovereign…”

Concluding Remarks

Christu Rajamony, in his book ‘Sacred Sites and International Law: A Case Study of Ayodhya Dispute’, has compiled in detail the international law obligations related to religious freedom, minority rights and cultural properties that all got trampled in the Babri Masjid Case. The Supreme Court of India confined itself to the pleadings before it and did not take into account international legal obligations of India with respect to international human rights law and international humanitarian law.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.