Ibn Khaldun

A brilliant polymath

Iqra Riaz

Abd al-Rahman ibn Khaldun, the well known historian and thinker from Muslim 14th-century North Africa, is considered a forerunner of original theories in social sciences and philosophy of history, as well as the author of original views in economics, prefiguring modern contributions. He is the originator of modern sociology and politics and also the one who gave political science a whole new outlook. He wrote a world history preamble with the first volume aiming to analyse all historical events. This volume, written in 1377, known as Muqaddimah or Prolegomena, was based on Khaldun’s unique scientific approach towards the subject and became a masterpiece in literature on the philosophy of history and sociology. The biggest merit of Khaldun lies in his revolutionary methodological thinking. He completely rejected the methodology of his ancestors, which made him the first “social scientist” in the strictest meaning of that term.

Introduction

Abd al-Rahman Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) was a great Arab historian and statesman who is often regarded as the founding father of modern sociology, historiography, demography and economics. He was born in Tunis, Tunisia. His family traced its origin to a south Arabian tribe that entered Spain in the early years of the Muslim conquest. His political theory is part of his description of ‘umran’ in the specific sense of ‘civilization’. His philosophy is deeply rooted in the traditional beliefs and convictions of Islam which also reflects in his work. The book Al-Muqaddimah (Prolegomena) is regarded as his magnum opus. The central idea of the book is based on the generalization about the collective human behaviour. He presented views on the following themes:

- Cyclical Theory of Empires or Theory of Rise and Fall of Empires

- Asabiyyah―Social cohesion

- Theory of State

Theory of Rise and Fall of Empires

In his theory of rise and fall of civilizations, Ibn Khaldun describes the process of dynastic development. He says, “The dynasty has a natural term of life like an individual.” The idea his theory of rise and fall of civilization revolves around is encompassed in his concept of ‘asabiyyah’ which depicts a specific concept of social dynamism: tribal solidarity is the motor of renewing bloodless urban structures and institutions.

First, ’asabiyyah’ appears as the very secular foundation of social dynamics between tribal egalitarianism and dynastic power construction. This denotes an ambiguous field of tension between solidarity and power. The concept is grounded in egalitarian kinship and brotherhood relationships, in which the extent of social cohesion becomes largely dependent on solidarity sentiments, group feeling or ‘we’ feeling and socio-ecological conditions.

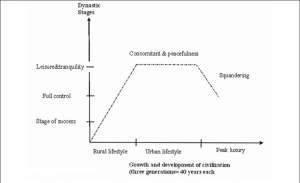

Ibn Khaldun argued that ‘asabiyyah’ in general is the moving force in social development; in a way, as an absolute turning point for gaining superiority of men, tribes and nations over others, it moves towards kingship and lack of ‘asabiyyah’ leads to loss of power. He argued that the term of life of a dynasty does not normally exceed three generations of 40 years each. The first generation possess characteristics like uncivilized rural life (badawa) such as hard conditions of life, courage and partnership in authority. That’s reason why the force of ‘asabiyyah’ or social cohesion is maintained in the civilization.

In the second generation, the conditions are changed due to the change of lifestyle from rural to urban. In urban life, everything becomes more specialized and there exists a division of labour which leads to the weakening of ‘asabiyyah’.

The third generation completely indulges in the individualistic lifestyle and the authority of a ruler declines. In such conditions, ‘asabiyyah’ collapses completely. Ibn Khaldun states, “Man seeks first bare necessities. Only after he has obtained (them) does he get to comforts and luxuries. The toughness of nomadic life precedes the softness of sedentary life.”

Thus, a dynasty can be founded and established with the help of social solidarity, group consciousness or sense of shared purpose relied on the concept of tribalism and clanism. But ‘asabiyyah is neither necessarily nomadic nor based on blood relations, rather it resembles the philosophy of classical republicanism. The establishment of royal authority and the foundation of dynasties are goals of ‘asabiyyah’. The process can be described in terms of success as the overthrow the opposition and the appropriation of royal authority from the preceding dynasty. Then comes the complete control in which a ruler gains complete dominance over his people, claims royal authority or domination all for him, and prevents them from having a share in it.

Then, the stage of leisure and tranquility come for the authority in which it enjoys fame and stability. In this stage, the ruler adopts the traditions of his predecessors and follows closely in their footsteps. The ruler wastes on pleasures and amusements and acquire low-class followers. The dynasty is seized by senility and the chronic disease it can hardly ever rid itself of, for which it can find no cure and, eventually, is destroyed. Provincial governors gain control over the remote regions when the dynasty loses its influence there. Each of them attempts to found a new dynasty to gain the royal authority and then the cycle goes on again.

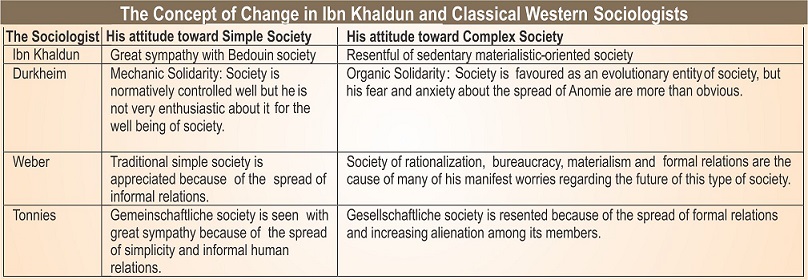

The dichotomy of ‘sedentary life’ and ‘nomadic life” presented by Khladun can be related with the contemporary concept of ‘gemeinschaft’ and ‘gesellschaft’ given by the late sociologist Tonnies.

Theory of State

Ibn Khaldun distinguishes three kinds of state according to their government and purpose: government based on the divinely revealed law ― the ideal Islamic theocracy – government based on a law established by human reason; and, government of the ideal state of the philosophers.

- Ideal Islamic Theocracy

In his ideal type of governance structure, Ibn Khaldun has given importance to the theocratic states which would govern on the principles of ‘Shariah’ and ruled by a ‘Khalifa’― caliphal authority. According to him, the caliph is the most suited and chosen person of God who would work to attain the utmost happiness in the theocratic state as Aristotle mentioned in his ‘Polis’ that the attainment of happiness is the purpose of politics in a society. According to Rosenthal, Khaldun terms this association of man and God as necessary for mankind.

- Government based on Reason

The second preferable state, according to Khaldun, is the one based on human reason where manmade laws and regulations are imposed on the society to control the behaviour of its people. Khaldun states “… society is an organism that obeys its own inner laws. These laws can be discovered by applying human reason to data obtained either from historical record or by direct observation. These data are fitted into an implicit framework derived from his views on human and social nature, his religious beliefs and the legal precepts and philosophical principles to which he adheres. He argues that more or less the same set of laws operates across societies with the same kind of structure. These laws are explicable sociologically, and are not a mere reflection of biological impulses or physical factors. To be sure, facts such as climate and food are important, but he attributes greater influence to such purely social factors as cohesion, occupation and wealth.

Government of Philosopher

Khaldun then preferred the government of a philosopher as already propounded in the political teachings of Plato. Here the philosopher, according to Khaldun, would rule according to reason, divine law and temporal law.

Critical Acclaim

Comparing with the other Islamic theorists, Khaldun presented his views based on more pragmatic and empirical basis as his theory of rise and fall of civilizations correlates with the human behaviour that endeavours to achieve excellence through power but have to face decline and decay. Though, the concept of social solidarity and in-group feeling is necessary to maintain the cohesiveness of a particular form of state the concept is impractical in the modern nation-state, because the contemporary socio-political realms rely heavily on the realistic school of thought. Machiavellianism and Hobbesian perspectives where the ruler, or supreme sovereign in the form of state, manipulates the power structure to create and maintain factions and cleavages among the masses in order to hold or dominate the power corridors. Moreover, the concept of theocratic state given by Khaldun is absolutist though he talks about a benevolent ‘Khalifa’ or caliph which would follow the ‘shariah’ but this concept has dictatorial hues. In contemporary political territories, this concept is impractical, though it is followed by some Islamic countries but they are more prone to perpetuate their powers instead of searching a mechanism to create an utmost happiness for the people.

Adam Smith as a Khaldunian thinker

Not only Khaldunian ideas, but the methodology behind them is also truly original, since it relies on abstraction and generalization. Khaldun gives us the economics of 14th century North-Africa and numerous relevant issues. He addresses questions for which we don’t have a single solution even in the 21th century. Khaldun helps us to bridge the gap in history of thought showing the importance of medieval Islamic culture. He also helps to understand the relationship between Islamic economics and other schools of thought being a theoretical common ancestor.

It’s not known for certain that Adam Smith or any other classical scholar hadn’t been inspired by Khaldun’s work when developing their own theories. Among others we have to uncover this information – which lost in the Great Gap – as well, in order to discover a new narrative which is closer to reality.

But why do we need a new narrative, rediscovering our past? The answer is simple: to avoid such superficial beliefs that Adam Smith (or Ibn Khaldun) is the father of economics, the development of economics started in the New Age to culminate in neoclassical thought, Khaldun already invented the Laffer-curve, the financial market effectively regulates itself or a big government is always bad for the economy – among others. Economists have to exercise self-reflection: the crisis of 2008 proved that gaps in the mainstream transform easily into policy mistakes.

With a new, more plural approach to history of thought the Alzheimer’s disease of mainstream economics can be cured which is badly needed in the 21st century.

“It is curious to compare Ibn Khaldun with Edward Gibbon who in his History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–88) presented that decline and fall as being due to barbarism and religion. By contrast, Ibn Khaldun presented barbarism and religion as the sources of empire, for, as we have seen, he believed that empires were regularly renewed by barbarian incursions and he believed that religion was a desirable supplement to ‘asabiyya for tribal conquerors who aimed to conquer an old regime and set up a new one.”

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.

Jahangir's World Times First Comprehensive Magazine for students/teachers of competitive exams and general readers as well.